It was mostly a man’s world – Alaska early in the twentieth century. But the women who came have fascinated readers since. A welcome new addition to books about Alaskan women is A Place of Belonging: Five Founding Women of Fairbanks, Alaska, by Phyllis Demuth Movius, fifteen years in the making. Movius talks here about how she transformed the project from a graduate thesis into a full-fledged book and what she discovered about pioneer women in contrast with Alaskans today.

So many fascinating women played significant roles in Alaska’s history. What spurred your interest in women of the northern frontier, and how did you decide to focus specifically on the founding women of Fairbanks?

My husband and I spend time at our recreational cabin on the Good[aster River near Delta Junction, in the Interior. When I manually pump water, haul firewood, and stoke the wood stove it gets me thinking about what life was like a hundred years ago when this was a standard day-to-day life style for many women in this country. In particular, I started questioning how women lived their lives in the north. Simultaneously, I began a graduate program in Northern Studies at the University of Alaska Fairbanks which allowed me to develop some of these thoughts. My thesis was about women in early Fairbanks and how they lived, and what role they played in the development of this community.

What factors helped you choose the five women featured in your book?

Anyone who does historical research knows that it takes a lot of raw material to produce a polished paper. So, to a degree, the amount of available archival material influenced specifically which women I chose to feature in the book. But, further than that, I wanted to present women who represented different levels of education, different backgrounds and socio economic levels, and various vocations. Thus, I chose a professional writer, a doctor turned lawyer, a homemaker and mother, an educator and social advocate, and a dreamer whose business plans were thwarted by an early death.

How long was the process of bringing this book from the initial concept into print? In what ways was the process different from that of your previous books?

This book began as my graduate thesis. After completion of my master’s degree the project stalled even though I had the idea in the back of my head that I would like to expand it somewhat and seek publication. Ultimately I got back into the research and submitted the manuscript to the University of Alaska Press which had published a previous book of mine. Due to some staff changes, the manuscript languished until Elisabeth Dabney came along with a flicker of excitement in her eyes at the idea of seeing this material in print. From beginning to end it was over fifteen years in the making! My previous publications were much more deliberate and required far less time to reach completion.

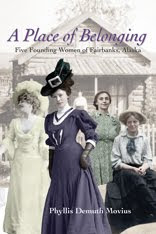

The book includes many fascinating archival photos, but the cover is particularly striking. Tell us about how it came to be, and how it reflects the content of the book.

The book cover was designed by Dixon Jones, a graphic designer at the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Dixon created the composition using a photograph of each of the five women whose biographical portraits appear in the book. The photos were black and white, but Dixon gave them color with a computer program which brought them to life. Dixon is obviously very talented, and I feel fortunate he was able to work on this project.

In the book’s conclusion, you note that your current life in a rural cabin is in some ways more taxing than that of pioneer women who embraced rather than shunned modern conveniences. To what extent do you think these early women would understand the notion of living purposefully “off-grid” and “away from it all”?

Fir of all, I must clarify that I live in a very modern house on the edge of Fairbanks. The rural cabin is strictly a recreational get-away.

I believe all of the women I present in this book would understand perfectly the necessary chores required to live comfortably such as stoking a wood stove and getting water from other than a faucet. However, for the same reason that I do not care to live full time at our rural cabin, the women of early Fairbanks did not enjoy the idea of living in isolation. From the beginning Fairbanks had a sophisticated infrastructure that included electricity, telephones, and maybe most important, a very active social structure. A look through copies of old Fairbanks newspapers indicates that the arts were prevalent in the form of theatre and concerts. Local government interested many who helped develop the mining camp into a permanent community, and there was no lack for parties of all kinds. And, almost any occasion such as the Fourth of July, or summer solstice warranted celebration. I am not sure that the women I present in this book could be considered to have lived purposefully “away from it all”… they were in the thick of things and were part of what made Fairbanks home to so many.