Review by Dan Branch

Tom Sexton has always seemed pretty Alaskan to me. But, he grew up in Lowell, Massachusetts. He served in the Army at Anchorage’s Ft. Richardson, and eventually obtained an MFA from the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. Then he established a Creative Writing Program at the University of Alaska, Anchorage. Twenty-four years later, he retired.

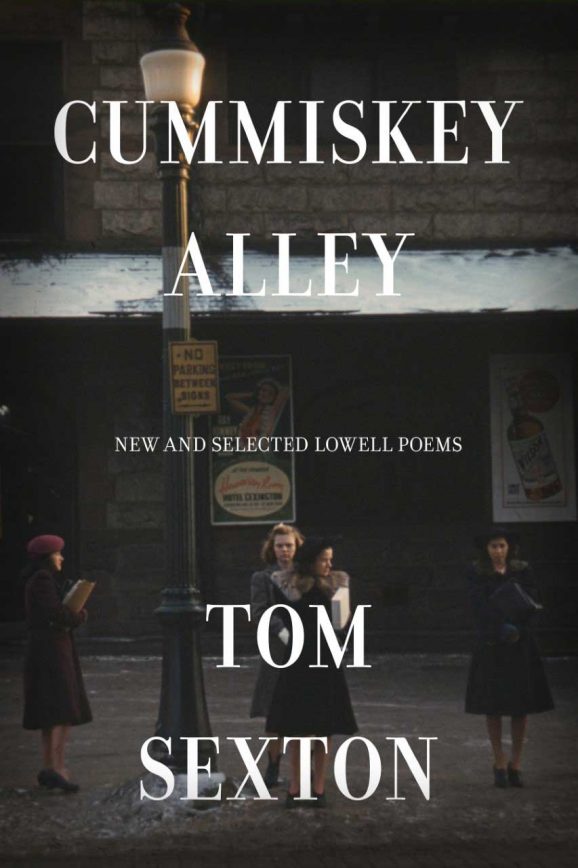

Last year, Loom Press from Massachusetts published a 132 poem collection by Sexton entitled, “Cummiskey Alley (New and Selected Lowell Poems).” According to the book’s editor, it “brings together the best of Tom Sexton’s poems about the place where he was born and grew up, the mill-lined river city of Lowell, Massachusetts—a place he never took his eye off, no matter his location.” The editor of the book points out that for “most of his life, [Sexton has] been in Alaska, writing, teaching, editing a respected literary journal (“Alaska Quarterly Review”), and always observing the large and small wonders in the world. He’s filled a stack of books with poems that tell us what he’s seen and heard and felt.”

I’ve always thought of Sexton as a nature poet. As the Cummiskey editor points out, Sexton has long been recognized as “…[A] premier poet of the natural world, from birds to mountains.” Perhaps because of my rural bush pride or a belief that nature must give each of us a unique understanding of its complex beauty, I’ve never read poems by Sexton or any other nature poets. Then friends mailed me a copy of “Cummiskey Alley.”

Wow.

In a blurb that appears on the back of Sexton’s new book, he is described as “an atavistic avatar of how to look hard yet write simply.” According to Merriam Webster’s dictionary, the word, “avatar” can describe the embodiment of a writer’s concept or philosophy. Dictionary.Com defines “atavistic’ as “the reappearance in an individual of characteristics of some remote ancestor that have been absent in intervening generations.”

“Cummiskey Alley” confirms Sexton as an atavistic avatar willing to avoid modern writing styles to capture, in strong but simple terms, the characteristics of the Lowell people of his youth.

Sexton begins his poem, “Triangle Luncheonette,” with the description of a fifteen minute lunch break he took while young and living in Lowell. “Your order was nearly ready when the baloney/ began to pop on the grill and it’s edges slowly/ darkened and began to curl, and the cook/ lifted it from the grill, added a little mustard/ and slid it down the counter with a flourish.” Then, as he did in many of the book’s poems, Sexton raises the subject matter of it with the ending sentence, “I imagine sharing one with my not-yet girlfriend,/ who, a bit of mustard in her teeth, would fall in love,”

Sexton punches up the poem with verbs like “pop,” and lines like, “slid it down the counter with a flourish.” I’d been happy with the result if the poem stopped there. But the last sentence, with it reference to a not-yet-girlfriend, makes you realize that the rich smell and taste of the sandwich inspired the customer’s thoughts of one he wants to love. (I grew up happily eating fried baloney sandwiches, which may explain why I want to share this poem with readers.)

Few of the poems in the book even mention Sexton’s connection with Alaska. “Pool Shark” is one exception. The first, and longest stanza of the poem describes how he and his friends, “duck-tailed and dumb from school” visited a Lowell pool hall where “[d]im-eyed and reptilian, Willie Provencher beat them, took their “palm-wet quarters one by one.” In the second stanza, he describes himself as a “fingerling anxious for the sea” who leaves Lowell and its pool hall for Alaska. Unlike the underfunded town of his youth, he finds “no small change in this Alaskan city/ where I live. Crude oil sets my table now/ and sharks wear silk, not threadbare overcoats,/ a place where few will bend to pick a quarter up.”

“Pool Shark” drives home the difference between Sexton’s crumbling Lowell, and bustling Alaska, where during the construction of the North Slope pipe line, prostitutes from the Lower 48 worked Anchorage’s Fourth Avenue and workers could collected enough money during construction season to keep then happy and underemployed each winter in their hometowns.

“Cummiskey Alley” reveals Sexton’s skills of observation and a powerful memory for solid details. It also reveals his appreciation for the richness of any human life. At the end of his bio piece called “On Becoming a Poet,” he writes about his last visit to Lowell: “In the morning as I was leaving, I noticed two children standing in front of the house across the street. They were waiting for a van to take them to school. I had heard and seen the yellow van the previous morning. An eyebrow of stained glass above the window where a woman was watching caught the early morning light.” Most people waiting for a ride to the airport would ignore the kids, not appreciate the mom discretely watching after her two children. Few people could turn it into a poem.