Gracie, my Irish-American grandmother, was the last child her mother delivered. Gram’s other six siblings left the home after school, believing that Gracie would stay with their mom until she died. That was the Irish way for the last born. They must have been angry when my Grandma Gracie took a winter train to Montana and married an Irish homesteader.

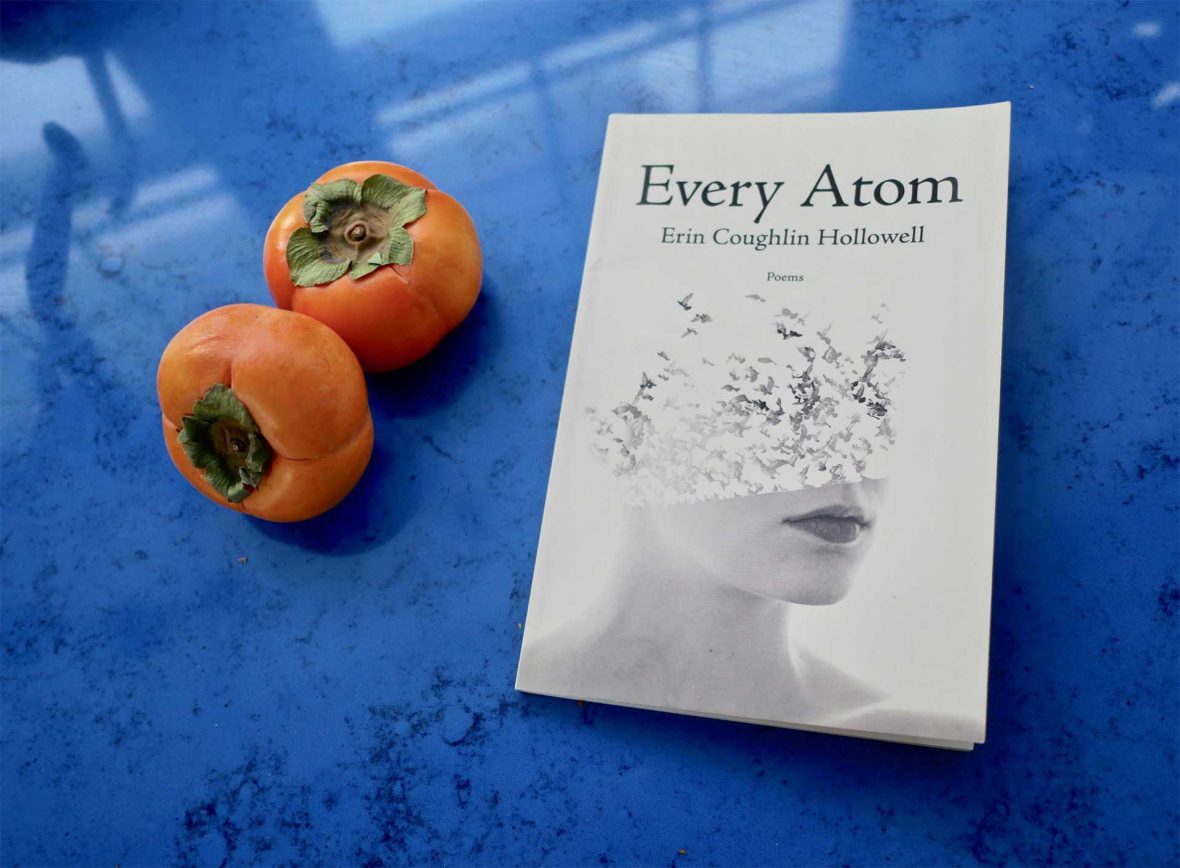

Reading Erin Coughlin Hollowell’s Every Atom, a book of poems about her aging mother, reminds me of my grandmother’s history. Like Gracie, Hollowell was her mother’s youngest, born when her mom was already forty two. Her mother suffered from mental illness when Holloway was a teenager. Because she was the youngest daughter, Hollowell had to spend her teenage years shopping for family and taking over other mom jobs. Mom-daughter tension was always high.

Hollowell’s mom’s mental capacities were declining when Hollowell began to write Every Atom. To help her father care for her mom, Hollowell give up a writer’s residency in Washington State. Writing poems that ended up in Every Atom helped her to better understand her mother and her own relationship with her. She recognized their similarities, which made it easier for Hollowell to deal with her mother.

Walt Whitman poem, “Song of Myself” inspired Every Atom. The book’s title and that of every one of it poems are quotes from “Song of Myself.”

Hollowell begins her poem “A Uniform Hieroglyphic” by describing her mom as “sitting/ beside the man she doesn’t know/ even though she has slept to the cadence/ of his breath for more than seventy years.” Every Sunday mom sits by him in their house while their children visit. When the children speak, she only hears “the braying/ of beasts that sounds only slightly/ familiar.” She is still able to maintain a composed face and even share “stories piled up as a shield/ against people who have shifted…” But the poet knows that for her mother, “[o]nly the small room is left, curtains/ drawn, gracious darkness shifting into/every corner, and the world/ a uniform hieroglyphic beyond the door.”

To understand the meaning of the “a uniform hieroglyphic,” I retrieved my battered copy of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and searched “Song of Myself” for them. The words in Hollowell’s title appear in the sixth chapter of the poem, where Whitman is trying to explain to a child the kind of grass the child carries in his hands. After noting how grass is “the handkerchief of the Lord” and a uniform hieroglyphic “[s]prouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones], Whitman concludes that it is also “the beautiful uncut hair of graves.”

The New Oxford American dictionary defines hieroglyphics as “enigmatic or incomprehensible symbols.” Perhaps Whitman knew this when he included “a uniform hieroglyphic” into his definition of “grass.” Hollowell’s use of the phrase in her poem suggests that for her mother, the world had become an incomprehensible place beyond her door.

One of the poems in Every Atom begins with a stanza written in Whitman’ style. The first section of the poem, “Nor any more heaven or hell than there is now,” connects descriptions of things together. (“How the light slices across/ leaves so new they purl and shine./ How two swallows flaunt above/ me, carving wedges of blue. How if/ I wanted I could climb/ the hill and keep walking on paths/ animals have made into green./ Walking into silence except for wind/ and birdsong.”)

Hollowell changes her writing style in the second and final sections of the poem, which describe the unpleasant and confused experiences of a patient named Rita in one section of her mother’s hospital and her experience being next to her mother in another section. This poem made me wonder if Hollowell would sometimes find relief from the stress of a visit by imagining walks through beautiful, heaven-like country sides.

While we talked about Every Atom, Hollowell told me that the book helped her to recognize similarities between she and her mother. This granted her more success in dealing with her failing mom. Reading the book should do the same for the many adults trying to help their aging parents. Hollowell’s poems, full of rich, symbolic images, also provides a collection of well written puzzles that can be solved by re-reading Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself.”

Erin Coughlin Hollowell is a poet and writer who lives at the end of the road in Alaska. Prior to landing in Alaska, she lived on both coasts, in big cities and small towns, pursuing many different professions from tapestry weaving to arts administration.

Hollowell earned her MFA from the Rainier Writer’s Workshop at Pacific Lutheran University in 2009. She received the Rona Jaffe Scholarship in poetry for the Breadloaf Writers’ Conference in 2010. In 2013, she was awarded a Rasmuson Foundation Fellowship by the Rasmuson Foundation and a Connie Boochever Award by the Alaska State Council on the Arts. She was one of the inaugural recipients of the Alaska Literary Awards in 2014. She was awarded residencies at the Vermont Studio Center and the Willapa Bay Artist in Residency Program in 2014. In 2017, she was awarded a second Rasmuson Fellowship to work on her third book.

Currently, Hollowell is the executive director of the Storyknife Writers Residency, a residency for women writers being developed outside of Homer, Alaska. She is on the faculty of the Kachemak Bay Writers’ Conference and the University of Alaska Low-Residency MFA Program. Her work has most recently been published in Talking Rivers, Rust + Moth, Alaska Quarterly Review, Weber Studies, Terrain: A Journal of the Built and Natural Environment, Sugar House Review, and Prairie Schooner.

Pause, Traveler, her first book-length collection, was released in 2013 by Boreal Books, an imprint of Red Hen Press. Her second collection Every Atom was released from the same press in 2018. Her chapbook, Boundaries, was published in January 2018 by Dancing Girl Press.