|

| Leigh Newman, author of Still Points North |

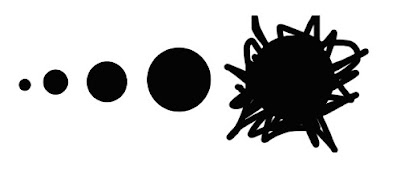

I’d like to take a minute to talk about fear. Specifically, the black burning ball of fear that goes hurtling through my soul every time I think about writing. The ball gets larger and more insane-shaped in direct proportion to the form that I’m writing in:

The ball also gets smaller in relation to my understanding of the form, or what I like to think of as “do-I know-the-hell-I’m-doing?” (Sadly most of my “do-I-know-what-the-hell-I’m-doing?” has no correlation with how much time I’ve spent on it or what success I’ve had; I have spent more time on never-finished short stories than anything else, including Still Points North.) The size of ball also shrinks and enlarges, over and over, as I write or begin to think about writing or even listen to another writer talk about writing, eventually ping-ponging through my being until I sometimes have to leave the room and go be around loud, drowning music. Or small children. Or cheese fries.

Perhaps you can relate?

Now wander with me, if you will, to another subject: Alaska. At sometime or another somebody always asks an Alaskan writer how Alaska influences her writing (besides setting). When I’m asked this question, I usually talk about growing up in the wilderness and how it does something to your way of seeing things: big panoramic landscapes and smaller, more visceral things such as…river mud when you’ve been sitting in it as a child for hours, having eaten some of it by accident, having lost one boot to its murky mucky depths, having felt something floating around down there by your frozen naked toe—a zombie salmon, maybe, with evil shark teeth. While your dad goes on blithely catching yet another silver.

Other times I get disoriented by this question and turn pretentious and start using the word “nature.” I can’t talk about nature without talking about it as if it were Nature or maybe Nature; the word, when uttered, immediately goes Masterpiece Theatre on me, down to the wing chairs and crackling faux fire. I say what I mean much better when I stick with words like alder, mosquito, mosquito, mosquito, bald eagle catching fish.

What I’ve always wanted to talk about, however, is fear and how fear functions in the survival stories that most of us have. Everybody in the world has these stories—incidents with missed stop signs or drunk drivers or scary high fevers. But living in Alaska seems to provide people with a slightly higher number of them. When I think back to the moose I harassed as a kid or the glaciers we crossed without ropes, I can’t help wonder as to how and why I didn’t die.

In my New York life and in my travels around the world, I also wonder about this. And I think—but I’ll never be sure—that most of my not-dying probably has been due to 1) acting before the fear took hold and 2) mojo. A recent example: while I was fishing on some slick boulders at the end of a jetty, my loyal—if limited and slightly insane—dog, Leonard leapt with excitement about the waves—and instantly fell into a gap between two slabby rocks. On instinct, I dove into the crack, groped madly around, got hold of his collar, and pulled us both out. This was not bravery. It was acting without thinking, without any logic even, except for: get dog, get out.

Which is where mojo comes in. A few seconds later, as Leonard and I panted for breath, a monster wave rolled over us. If we’d still been in the gap when that happened, it would have been, as the wise men say, not good. As it was, it was still not good….but we lived. And staggered around for the rest of the day with salt water in our inner ears.

Though I can’t see inside his brain, I suspect my father also relied on these same two factors for most of his Alaskan parenthood. Some examples: the time he caught me before I fell out of the raft and into the Class 4 rapids. The time he swam against the tide after our floating-away floatplane. The time, at 20,000 feet in the air, when he pointed the nose of the plane at the ground to keep us from drifting up to 21,000 feet and falling out of the sky. All instinctual actions that, when combined with mojo, worked. We lived.

There is something in this act-before-thought progress that I hope corresponds to writing. Writing, of course, is not survival. I don’t want to suggest that. Writing is a life’s pursuit but it’s not life. Life is much, much, much more important. (How many authors mention books on their deathbeds?) That said, writing does require the production of letters and periods and quotation marks before that black ball of fear rolls through you, flattening every word.

So how to act? How to move your pen or hands? I have no proof, but I think the answer might be found with Leonard. I acted to save my dog. Just as my dad acted to save me. It’s hard to act without thought when it comes to ourselves, but not when we’re acting for the benefit of somebody we love. Which means that when it comes to writing, it is easier to fling ourselves into it when we’re pursuing a love object: a character or a setting or a story that fascinates us, no matter how beautiful or scary or repulsive or overlooked.

On the other hand, when we’re pursuing being a good writer or a respected writer or a famous writer, when we’re pursuing punishing that asswipe bully from second grade or proving Mom wrong about law school or winning the National Book Award, I suspect that we stop and think before flinging ourselves in harm’s way—creating just enough time for the black ball of fear to roll through the corridor of our minds, gathering heft and speed. Because we’re acting to save an idea about ourselves, not a real flesh-and-blood thing, which is what a story becomes if you’ve fallen in love with it.

And after that, it’s up to mojo. Also known as that mysterious and inexplicable force which—when it’s with you—keeps the coffee mug from toppling over onto your keyboard.

Leigh Newman, author of Still Points North, will be in Alaska this week, and there will be many encounter opportunities. On Wednesday, April 24, 2-3 pm, she will be live on air with Lori Townsend and Sherry Simpson on Hometown Alaska, and at 5-7 pm the same day, she’ll be giving a presentation and signing books at the UAA Campus Bookstore. On Thursday, April 25, she’ll be on television for an interview with Doreen Lorentz on Alaska Political Insider 4-5 pm, and then will be giving a 49 Writers craft talk at Great Harvest at 7:30pm. On Friday April 26, 7 pm (arrive 6.30) she will be giving a reading and reception together with Eowyn Ivey at Cyranos. On Saturday, April 27, 6 pm, she’ll be at Gulliver’s Books in Fairbanks for a presentation and signing, and on Sunday, April 28, 11 am-1 pm, she’ll be at Barnes and Noble in Fairbanks signing books.

Wonderful piece. Thank you, Ms. Newman, for your honesty and encouragement.

That unwieldy black ball of short story fear is a bugger. Any advice on eradicating it is appreciated. Thanks!