If I were asked  to choose (hypothetically) one book to take with me into solitary exile on an island, I’d ask if I could bring my fishing tackle instead. But if that wasn’t allowed, I would choose the heaviest anthology of short stories I could find. Maybe The Story and its Writer edited by Ann Charter. Or The Norton Anthology of Short Fiction.

to choose (hypothetically) one book to take with me into solitary exile on an island, I’d ask if I could bring my fishing tackle instead. But if that wasn’t allowed, I would choose the heaviest anthology of short stories I could find. Maybe The Story and its Writer edited by Ann Charter. Or The Norton Anthology of Short Fiction.

What’s so great about short stories? Well, Edgar Allen Poe said that “the brief prose tale” was the form that “should best fulfil the demands and serve the purposes of ambitious genius.” Okay, I’m neither ambitious nor a genius, but I do love reading and writing short stories. As for poetry, he said that standard short poems were pleasantly exciting, but were often so brief as to “degenerate into epigrammaticism.” And really long epic poems (he gives Paradise Lost as an example) he said become wearisome, the poet having had to try too hard to keep the verse floating for the life of the huge undertaking.

What of the novel? He says “As the novel cannot be read at one sitting, it cannot avail itself of the immense benefit of totality” which is offered by a short story. “Worldly interests,” Poe continues, “intervening during the pauses of perusal, modify, counteract and annul the impressions intended.” In other words, you just have to put a novel down sooner or later to eat, sleep, or get a cold beer, and that kills it, because you get distracted by other things before you get back to it. That interruption destroys the feeling of being so completely immersed in a story, that the reading experience feels like a “vivid and continuous dream,” as John Gardner put it.

While reading a short story, Poe says, “without interruption…the soul of the reader is at the writer’s control.” Not just the reader’s attention mind you, but his very soul! Wow. He’s giving short stories nearly Satanic power. If that doesn’t make you want to write them, I don’t know what’s wrong with you. Of course, it’s no big surprise that Poe, the staunch defender of the form, was himself best known for—guess what—his short stories.

Conventional wisdom has it that people who like short stories have short attention spans. But I’m not sure that’s all there is to it. My physical therapist is constantly chastising me for sitting hunched over this laptop for uninterrupted hours and hours, the bad posture further aggravating my neck and back problems. Am I playing video games? Perusing Facebook? Shopping online? No. Most of those long hours at this machine are spent working on either my own writing or student stories. I’ll happily concentrate on one thing for long periods of time. Too long. And I can easily stay up half the night devouring a book of short stories. It’s not a matter of attention span. It’s a craving for the rhythm and the structure and for what Poe called the “totality” of the reading experience that short stories provide

How did I end up like this?

I was a small independent wallcovering contractor for nearly forty years. Instead of working in a career that spanned years, even decades, I did small jobs, most of them taking only days or weeks. And with each one, I could only submit my invoice when the last square foot of wall was covered. Raymond Carver’s advice to short story writers was, “Get in, get out, don’t linger, move on.” For my whole working life, my business plan was “Get in, get out, don’t linger, get paid.” Such conditioning does not prepare a person for the long haul of novel-writing.

A second reason may be because I’ve been married for 45 out of my approximately 48 years of adulthood. Think about it: when I pick up a book or sit down to write, the last thing I’m looking for is a long-term relationship. I’m looking for the literary equivalent of a one-night-stand. Or at the very most, a brief passionate affair. At the end of the day, I get into bed with a New Yorker (the magazine, not a citizen of the Big Apple). The next night I might hit the sheets with the current Atlantic Monthly or Harper’s magazine story, each one embraced and then thrown over for something new and exciting the next night. This does not encourage reading novels, let alone writing them.

A third influence may be this: in the spring of 1987, returning to college after twenty-years of construction work, I took a “survey of the short story” lit class. It was the most exciting and memorable class I’ve ever taken. I was like a duckling imprinting on the first literary form I really set my eyes on.

We started with Hawthorne and Poe, and worked our way through the 19th Century and into the 20th with writers like Ambrose Bierce, Melville, Tolstoy, Twain, Sarah Oren Jewett, De Maupassant, Chekhov, Willa Cather, James Joyce, Katherine Ann Porter, and of course Faulkner, Hemingway, and Fitzgerald.

Moving through the Moderns, we waded into the mid-century greats like Isaac Bashevis Singer, Eudora Welty, John Cheever, Shirley Jackson, Grace Paley, and the great, great Flannery O’Connor. It was so exciting to follow the history of the form leading up into my own time and contemporary writers: Ursula K. Le Guin, John Barth, Donald Barthleme, Alice Munro, John Updike, Raymond Carver, Ann Beattie, Margaret Atwood, Joyce Carol Oates, Tobias Wolff. And it was even more exciting to know that they were out there, right then, writing those fabulous things called short stories.

I was a goner, unable to control my appetite for them, a short story junkie forever.

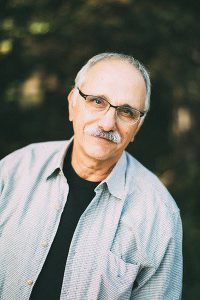

Richard Chiappone is the author of the collections Water of an Undetermined Depth, Opening Days, and Liar’s Code. His stories have appeared in magazines including Alaska Magazine, Playboy, the Sun, and Gray’s Sporting Journal, along with literary magazines including the Crescent Review, The Missouri Review, South Dakota Review, ZYZZYVA, and others. His work has been featured on BBC Radio, and made into a short film featured at international film festivals. An Alaskan since 1982, he is proud to be a member of 49 Writers, and lives in Homer with his wife and cats. He teaches fiction and nonfiction writing for the University of Alaska Anchorage, and for the Kachemak Bay Campus of the Kenai Peninsula College. His latest book, Liar’s Code, is published by Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. of New York City. It is available in both hardbound and electronic editions.