Step 1: READ YOUR BRAINS OUT

Move to a town famous for its writing culture. Maybe there’s a fancy MFA program you wouldn’t even try to get into, or a local history of invested writers, and nearly every barista slinging lattes and croissants has published a volume of poetry. Immerse yourself in the regional literature, devouring its canon’s paperbacks from the secondhand bookstore and library, ravenous as a spring wolf.

Step 2: WRITE A FIRST DRAFT

In love with short stories, finagle your way into a writing workshop with a lauded teacher, and write as if you think you deserve to be there. Turn in a short story. Blush with delight at the teacher’s initial praise—“this is good”—until he says, “but the ending’s no good, and you know what your problem is, right?” Watch as he bangs on the manuscript with a flat hand, your blush now embarrassment, because you have no idea. He tells you: “Your problem is, that’s not the end. This is a novel.”

Step 3: RESIST

Stammer. Profess your love for the short story. State that you have no idea how to write a novel. Panic. Put the story into a folder. Don’t think about it (length of time may vary).

Step 4: WRITE OTHER STUFF

Write short stories. Publish a few. Years after the first workshop, return to school for your MFA (at a smaller out-of-the-way program that will let you in, and give you some money in a town where not all baristas have poetry collections). During a fiction workshop, write another story, completely unrelated to the old story in the folder. A first-person, direct address three-pager, full of voice and swagger, and after you’ve read it aloud a few times, you have a niggling sense that the voice is familiar. You start to wonder if the girl (age 13) is the same girl from the story in the folder (age 9). How could that be? Unrelated by plot, written under totally different circumstances, by no stretch a natural outgrowth. But, hmm. The thought sticks. Put the 2nd story in your thesis collection. Put that in a folder. Start writing a different book.

Step 5: REVISIT OLD DRAFTS

Five years later, after your first book has come out (non-fiction, unrelated), attend a month-long residency in which your stated purpose is, in part, to figure out if you want to write a novel. You’ve always read novels, and now you take notes. Pull out stories, noodle around, wonder. Draft a few pages of an idea that doesn’t last. Something brings to mind the very old stories, in two different folders. Get them out. Your hunch that they are related still feels right. Now, where’s the rest of it?

Step 6: WRITE, REVISE

Spend five years working towards a full draft of what you finally accept is a novel. Your old teacher, now deceased, was right. The more you write, the more you can see the edges of it: the story, the characters, moving this way and that. A place emerges, develops. People rise to the fore, demanding attention, bringing a surprise, or they fall away, or they merge. Listen to them. Write when you can discern what they’d say, how they’d see. When you’re not writing (which is often, since you also have to earn a living), think about the characters. Let the story grow old in you. That first girl—the one who was 9, then 13—becomes a person, both distant and grafted, like a friend once dear to you who you haven’t seen in years.

Step 7: INVITE OTHERS IN

Widen the scope. You’ve basked for years in the novel as your own private world, shared only with your first reader, your spouse. After waffling, show your agent. Some admiration, some ideas, but: no love. This proves your old refrain first tried with the trusted teacher (“I don’t know how to write a novel”). Remind yourself there are many readers, many paths. Show the draft to a trusted friend (only one). She has love. She has ideas. Hmm. Listen to her input, read her comments, try to determine which insights matter to you and which will fall away. There’s still a problem with the ending. And the middle. Revise. Return to agent after a few years. Still, no love. If you revised further for her, you worry it wouldn’t be your novel anymore. Enter, crisis of confidence. Enter, stubbornness. Enter, boredom, defeat, worry. Entertain the thought that a certain arrogance of vision is making you obtuse and unreadable. Entertain the thought that you’re wrong about that. Invite in another close reader. She says, trust yourself. You don’t exactly, yet, but you do keep at the writing. Plugging away.

Step 8: BET ON YOURSELF

After the 3rd round with the agent who is smart, powerful, competent, well-connected, but does not love your novel, it’s time to decide. Go where the love is, advises a close friend. Or, leave where the love isn’t. You make a break. Cordial, mutually respectful, best wishes. Now you are a 46-year-old writer with no agent, no press, no contract, no contacts in fiction to speak of (your first book was non-fiction, why the hell did you not write another one of those?) Most of all, you are a writer with a weird novel that may or may not be any good, that you have been working on for over two decades. Revisit previous: stubborn.

Step 9: BECOME A TEAM

Ask writer friends for agent ideas. One replies immediately with a lead, she might be perfect. Query her. Wait anxiously. To increase anxiety, enter a global pandemic, and the shut-down of the publishing industry. The agent writes back. She read it, fast, actually. And here, finally, is the love. A long exhale. You realize how deeply you’d been longing for it, not just a contract, a second book, but for someone else to love these characters—by now, your people. Their own selves, who you treasure and think deserve to be seen. Sign a contract with the agent. Read the details, but mostly, bask in the love.

Step 10: BE PATIENT

This may take a hell of a long while (see: aforementioned pandemic, shutdown, protests, unrest, supply chain, delays). Books seem unimportant, or most important, depending on the day. After a year with many nibbles from publishers but no bites, suddenly, three offers come within weeks. All independent presses, with clout and passion. Sign with the one whose editor writes you an offer letter that makes you cry, because she loves, as your agent loves, as you love. Always, more revising: superb editor’s subtle comments trigger revisions that echo far. Two years of production. Cover design, email, layout, copy edits, email, marketing plans, more copy edits, blurbs, galleys, email, email. While this is unfolding, work on something new.

Step 11: RELEASE

Finally: here it is, the book. An object, crafted, printed, bound, out in the world, in your hands, in others’ hands—a smooth, finished thing, crisp pages, a life of its own. Within it, people standing up, speaking, asking to be known. The first time you hold it is almost exactly 25 years after the first lines were written. It was a novel after all. No problem!

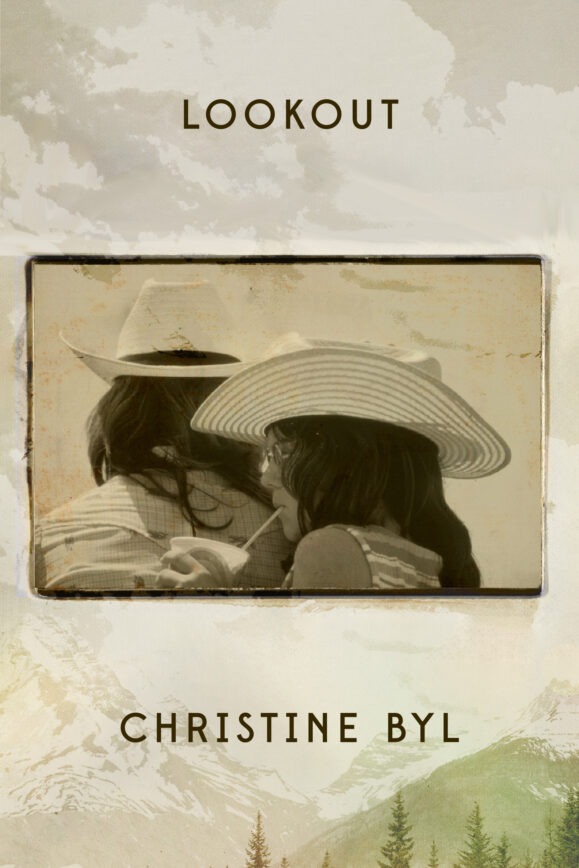

Christine Byl is the author of Lookout and Dirt Work: An Education in the Woods. Her prose has appeared in The Sun, Glimmer Train Stories, Crazyhorse, and others, as well as multiple anthologies. She has received support from the Rasmuson Foundation, the Alaska Literary Award, Alaska State Council on the Art, Bread Loaf and the Fishtrap Foundation. Christine lives in Interior Alaska, north of Healy, on Dene lands.

This was beautiful and inspiring—especially the willingness to leave one agent and find another who would loved and understood the book. Determination, persistence, bravery. Congrats Christine!

Thank you, ARL!

Well written inside look at the labor of love that writing is. I often think, if I’m lucky, I’ll publish my memoir by the 25th anniversary of events occurring. No agent. I’ll just self pub. But its still not what I want it to be and i wonder if it ever will be.

Congrats! I used to read your stories in various journals unbeknownst to anyone we worked with (Denali 2005-2006). Since we didnt really get along, I wouldnt let anyone know that. They were always top notch, as expected. I can’t wait to read your new work!

Thanks so much, Cindy! I’m glad to hear that you are plugging away on your project. It takes whatever it takes.

All the best,

Christine