I watched the ferry chug off toward Alaska every week from Bellingham, Washington while I was in college. I loved northwestern Washington, and the proximity of the Canadian border twenty miles up the road. Every time I watched that blue ferry leave, though, magnetic bits inside me pulled for points north.

I’d studied the maps, and read, and plotted that course north since I was a kid—I even got a little taste of it a month after I graduated from high school when my girlfriend’s mom surprised me with a last minute offer to take me with them on an Alaska cruise. The context was all wrong to encounter that stretch of coast that I’d wanted to see my whole short life, but I am grateful for the trove of moments that stuck, like watching tidewater glaciers calve in epic fashion, sending surge waves crawling out to rock the ship, or seeing my first breaching humpback. One afternoon while we were surprisingly close to shore in a deep fjord, someone spotted a brown bear on the beach through the window of the piano lounge. The pianist quit playing, jumped up, pulled a pair of binoculars out of his bench, and ran outside to watch the animal, all of us close behind. A funny spectacle, especially for a 17 year old kid from Idaho fresh out of high school who didn’t imagine that he’d be back there five years later on his own little boat, gathering the beginnings of an indelible, transfixing sense of place.

The cruise piqued—but certainly didn’t satisfy—my interest in Alaska. Two years later and a quarter mile from the ferry terminal in Bellingham, a particular volume in Village Books surfaced like a clue indicating much that I would come to care about in due time. It was From the Island’s Edge: A Sitka Reader, edited by Carolyn Servid and published by Graywolf Press (1995).

|

| Carolyn Servid |

The anthology collects work from the first decade of Sitka Symposium faculty members—poets, philosophers, novelists, naturalists, anthropologists, linguists, and others who “juxtapose aspects of the human experience that are seldom considered in relationship: the poetic imagination and the reasoned argument, and ultimately, the public shape of our private lives.” I would spend years reading the books of writers I found there: John Haines, Robert Hass, William Kittredge, Barry Lopez, Richard Nelson, Paul Shepard, Terry Tempest Williams, and others, including John Luther Adams.

Eventually, Alaska became my home, though I landed further north—and further from the sea—than I once imagined. It’s been story, though—from books, sure, but also from friends, coupled with my own story, or experience—that has made place of this most spacious of states.

Like me and so many of us here in Alaska, Servid came from afar and found home. In her book Of Landscape and Longing, she recounts growing up in a village in India as the child of American medics. Later, America felt ill-fitting and foreign. She writes about wanting and making home, and about displacement from the places that shape us. The book records something of the early intoxications that can come with the kind of subtle and grandiose encounters with wild nature that Alaska dishes up to most everyone who looks and stays.

Servid’s greatest contribution to literature, though, was founding the Sitka Symposium in 1984 and sustaining it for 25 years. Along with three other Sitkans, she “wanted to explore writing in the context of ideas,” not purely from a craft or technical viewpoint. Servid, along with her partner, Dorik Mechau, developed the program into an expanded, robust organization—the Island Institute.

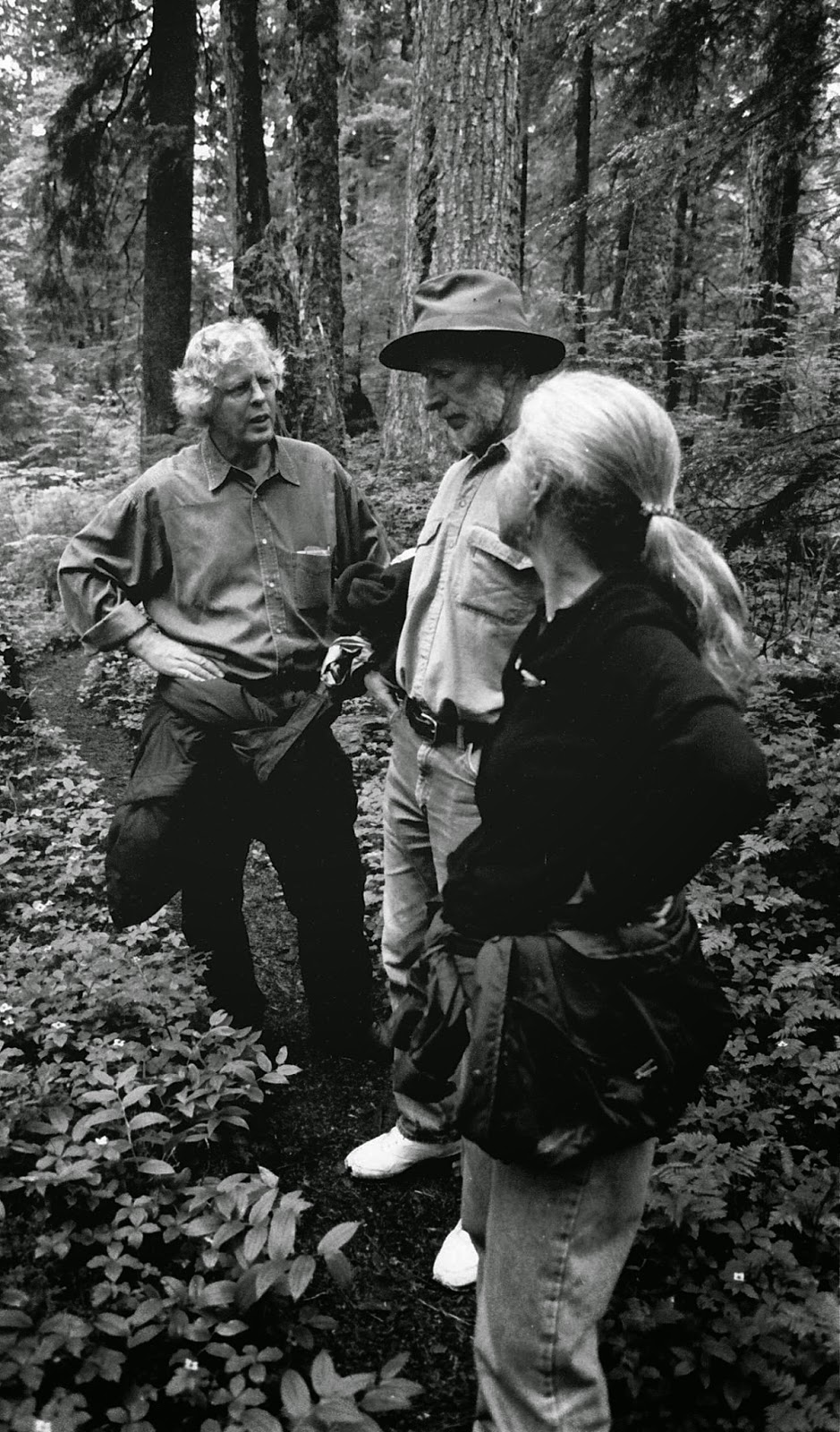

|

| Ted Chamberlin, Mike Mechau and Carolyn Servid in 1998 |

After 30 years at the helm of The Island Institute, founders Servid and Mechau retired recently. The second generation of staff, headed by Executive Director Peter Bradley, a dual U.S.-Canadian citizen, is organizing a 30th Anniversary Retrospective event in Sitka on Saturday, March 21st. They will honor the organization’s storied history while reconnecting people across the country who have been involved as participants and faculty over the decades. Featured speakers include David Chrislip, Vernita Herdman, Gary Holthaus, and Don Snow—all addressing different facets of the Institute’s past.

The program that launched the organization—the Sitka Symposium—was built on the power of language and story as tools that help us understand and discuss the world. Servid identifies threads of relationship between story, place, and community as constants in Symposium discussions over the years. For most of its history, they focused on the long term sustainability of communities, with all the environmental, economic, and political valences inherent in “the work of nurturing sustainable human cultures.”

When they started, the only other literary efforts in the state were in Fairbanks—they were running Midnight Sun Writers Series, and Servid says there was almost an atmosphere of competition, since they both happened in summer. UAA’s writing program hadn’t started yet, nor Kachemak Bay Writers Conference, 49 Writers or the Tutka Bay Writers Retreat, or NorthWords, or Wrangell Mountains Writing Workshop. Many esteemed Alaska writers presently involved across the state were early Symposium participants. Over the years, the Island Institute has also partnered with other organizations and schools throughout the state to pull off major literary initiatives, including the establishment of LitSite Alaska.

As communities in Alaska face complex challenges that echo and amplify something of Sitka’s strife in the early 90s when the local mill closed, the Island Institute has deliberately shifted away from a focus on sustainability to resilience. Servid said “sustainability has to do with maintaining a status quo, as opposed to being alive and adaptive to change, thriving in a fluctuating environment, and taking on the challenges that we’re going to be faced with given what climate change is going to throw at us.”

Though Servid’s achievements over 30 active years warrant more praise than they have received in Alaska, the Symposium has achieved national distinction. More than ninety guest faculty members have included some of the country’s finest writers on environmental and community issues as well as important emerging, Native American, and international voices. Poets, fiction and nonfiction writers, folklorists, anthropologists, scientists, teachers, and politicians have all been part of the mix—a deliberate variety to approach each year’s theme from diverse perspectives. Symposium participants—people of varied ages, experiences, and backgrounds—have come from over thirty states and as many Alaska communities. Robert Hass, a two-term U.S. Poet Laureate and faculty member, said the Symposium “is that ideal thing: home grown, community-based, sustained for years now by mostly voluntary and always inspired work, national in reputation, global in its concerns.”

The last full-fledged Sitka Symposium was held in June 2009, though a one-off reprise occurred with considerable modifications in 2014 after a five year hiatus. That gathering explored how dominant cultural narratives relate to contemporary challenges. It featured Winona LaDuke, Luis Alberto Urrea, Alan Weisman, and others.

Even in the wake of its founder’s departure, the Island Institute continues to pursue its mission through diverse programing, including an evolving residency program for writers. Housed for the last few years on the Sheldon Jackson campus, now owned by Alaska Arts Southeast, the organization itself is adapting to a changing economy, a changing literary tableau, and changes in leadership.

I’ll be back on Southeast water again during the Retrospective event, though I won’t reach Sitka, unfortunately. Still, it will feel fitting to think my way there from the decks of the M/V Aurora and M/V Matanuska ferries traveling between Juneau, Haines, and Skagway. It’s been almost twenty years since the first time I saw that stretch of water, and nearly that long since I discovered Servid’s first anthology in a bookstore in Bellingham. Part of my own work in the meantime of figuring out what home is, and how to live in a place and in communities in the context of great change, resonates deeply with the Institute’s core principles. I have seen the Island Institute’s mark—conspicuous and otherwise—throughout Alaska’s literary landscape, and am certain that landscape is stronger for it. I also believe that the Institute’s own resiliency will not only model that ideal but serve as testimony to Servid and Mechau’s vision and efficacy.

Jeremy Pataky is the author of Overwinter (University of Alaska Press, 2015) and a founding board member of 49 Writers. He earned a BA at Western Washington University and an MFA in poetry at the University of Montana. He divides his time between Anchorage and McCarthy, Alaska, and works as a consultant with an emphasis on arts and culture.