“What’s in a title?” riffs David Petersen in Writing Naturally, his down-to-earth guide for aspiring nature writers. A good title, he answers himself, must grab a browsing reader’s attention, foreshadow what is to follow, and prompt you to flip over a book for its back cover text or, more likely nowadays, click on its link for a synopsis.

Titles have long been considered to be the single most important piece of advertising for a book, from Daniel Defoe’s sixty-five-word tapeworm summarizing The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Of York … to the iconic, minimalist, then-still futuristic 1984 of George Orwell’s masterpiece.

Nonfiction book titles in particular are influenced by search engine and keyword optimization, even auto-fill functions, read: marketability. This is where the vision of writers and that of editors and their sales teams frequently clash. Lengthy titles—hard to memorize for an overwhelmed book-buying public—can even fall prey to a graphic designer’s concerns.

“Writers have far more control over what’s in their books than what’s on them—the cover art, blurbs, jacket copy, but especially the title,” bemoans Tony Tulathimutte in a Paris Review piece gloriously captioned “Title Fights.”

Neither the illustrious nor the infamous are exempt. Susan Orlean’s The Millionaire’s Hothouse—a title she loved dearly, though no one else seemed to—became The Orchid Thief. She had every single one of her original book titles changed. Hitler’s Mein Kampf was at first Four and a Half Years of Struggle Against Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice. And Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex inanely disguised as The Birds and the Bees.

Authors seldom see such meddling as improving their goods. “An editor’s habit of replacing an author’s title with one of their own,” John McPhee effervesces, “is like a photo of a tourist’s head on the cardboard body of Mao Zedong.”

I, too, have my tales of renaming woes besides serious doubts: a publisher trusts that I can deliver 90,000 publishable words but not a mere ten that sum those up pithily? We’re wedded to our titles. They’re our business cards, the equivalent of the movie industry’s elevator pitch. Still, “Authors, as a rule, are poor judges of titles and often go for the cute or clever rather than the practical,” as Nat Bodian states in How to Choose a Winning Title.

Easy to say for him, a writer in the self-help genre.

Adepts of creative nonfiction have a row much harder to hoe. We seek to appeal to the literary minded, kin to the lovers of short stories and novels. We defy an anonymous Little, Brown editor’s verdict that “In today’s nonfiction climate … blunt, foolproof subtitles are near mandatory” or Tulathimutte’s that “with nonfiction there can be less room for mystery and poetry.”

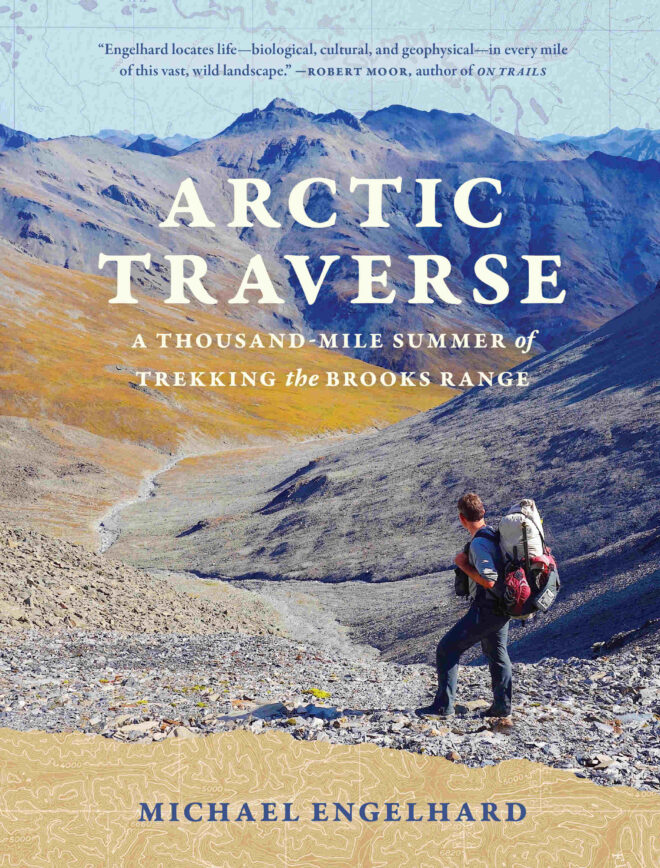

The second half of my new memoir’s title, Arctic Walkabout, smacked of cultural appropriation, according to the editors, though the contested word crops up in dictionaries outside its Australian context and seemed to capture the initiatory nature of my thousand-mile trek and my sense that by walking and writing I was singing a landscape into existence, much as Bruce Chatwin described in Songlines. Under pressure, it morphed into the somewhat bland Arctic Traverse.

I’d also subtitled No Walk in the Park, a collection of Grand Canyon essays, A Redrock Guide’s Quests, Misadventures, Obsessions, and Odd Observations, alluding to 18th- and 19th-century exploration accounts while hoping to introduce a note of mild humor and self-deprecation, which color my writing voice. The editor felt it was too much of a mouthful and selling short the book’s lyricism and depth. I rejected his suggestion Reflections of a Redrock Guide as too Thoreauvian, lacking action. It flashed before me images of a wannabe sage sitting in his garret. Jokingly, I bounced Maunderings and Meanderings of a Redrock Guide back to him, which—surprise, surprise—he was excited about and which became the approved subtitle. I came to like it for the dualism of physical and mental motion (and the grouch factor in “Maunderings,” which captures an aspect of my bearish persona), and for its contribution to reviving a word now fallen out of fashion. Then I saw its redundancy with “Meanderings” and its negative connotation (“to speak disconnectedly”) and heard that I should have “Grand Canyon” somewhere on the cover if I wanted the book to sell well there, so I changed it again.

My biggest reality check came with How Joyous His Neigh, my intended title for

an anthology of western-horse stories and essays. My wife and editor both pointed out how that might land the book in the erotica section of stores—until then, I’d never noticed the innuendo. Call me naïve. The line came from a Navajo warrior praising his horse in song, after all, and I found it poetic. (The book was published as Unbridled.)

We adventure / travel / nature writers all dream of hook-and-sinker doozies like Tim Cahill’s Pecked to Death by Ducks and Pass the Butterworms, and of publishers signing off on those. To gear myself against rejection, I now sometimes test title alternatives in mini focus groups consisting of readers, fellow writers, and booksellers. Alas, they seldom agree on a single favorite. Mao turns out to be a many-faced son of a gun.

Michael Engelhard, the editor of four anthologies (one, of flash fiction and nonfiction), is the author of Ice Bear, a cultural history of an arctic icon, as well as of two essay collections—including What the River Knows—and the account of his solo Brooks Range trip from Canada’s Yukon border to the Bering Strait, Arctic Traverse. Trained as an anthropologist and having worked twenty-five years as a wilderness guide, he lives on the outskirts of Fairbanks, Alaska, surrounded by lynxes, porcupines, and owls. He believes that making readers laugh can sweeten bitter environmental pills.

Fun. And you should all read Michael’s latest. Pithy indeed.

Dear Michael

Your post made me laugh. A title for a book can be one’s own compass for the stories told. I have changed my book title at least ten times while writing my book and in the end, chose the first one I had decided on.

Having a title not of your choice must be tough. In the end I think a title is like a book cover. It can draw a reader to it at first, but in the end what really sells a book is the actual content inside.

Hi Annette,

I’m glad it brightened your day a bit. “A man can’t just sit down and cry, he’s got to do something,” the botanist Bonpland (a friend of Alexander von Humboldt) wrote, and the whole publishing business can be rather frustrating. I too find that the title (even if only a working title) keeps me focused on a book’s gist. And, ideally, a title and cover art work hand in hand to reinforce the message of what a book is all about.