Blurbs sell books. I suppose that seems obvious, but early in my writing career, I thought publishers sold books. Period. So although I met some great writers in my genre right after my first novel came out, I never thought of asking them to blurb my second book. Neither, apparently, did my publisher.

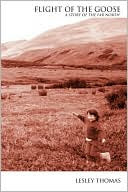

Hindsight being what it is, hefty blurbing caught my eye when I picked up a copy of Lesley’s Thomas’s Flight of the Goose. And I recognized names: Nick Jans, Heather Lende, Fred Bigjim. Instant cred. I’m looking forward to reading the novel, billed as “a tale of cultural conflict, spiritual awakening, redemption and love in a time when things were, to use the phrase of an old arctic shaman, ‘no longer familiar’.”

Thomas, who now lives in Seattle, shares her experience of getting blurbs in a two-part series for 49 writers.

Getting blurbs or endorsements for my Alaskan Arctic novel Flight of the

Goose turned out to be fascinating and satisfying and led to great

friendships, but it also made me anxious. First, I was raised with and later

married into powerful cross-cultural and gender-linked values that forbid

bragging and showing off, competing, trying to “get ahead of the herd,”

asking for help – especially from strangers – and groveling. Selling

stuff – with the exception of good, honest fish or handmade crafts that

supported noble causes – was crass and the work of parasitic slime bags.

Elitists were not respected and the literary elite were off in

another world, as far away as Pluto.

You might guess I was raised in Alaska. Yes, as far away from the elitist slimebag world as you could get: on a small wooden troller in the Inside Passage and in Bering Strait villages. Fairbanks, Sitka and Nome were the big cities of my formative childhood, places where dreaded commerce took place. When I went Outside it was to live on a subsistence homestead far from the Madding Crowd and full of

ancient Puritan/Native American relatives who reserved bragging for patriarchs.

Marketing was worse than bragging, something hucksters with raincoats or hoity toity city slickers did. Posting on the Internet was worst of all because it

was bragging to entire world. Maybe you could run an ad for a used guitar,

but you couldn’t praise the guitar. This makes job interviews difficult for

people of my Viking Sami Hillbilly Inupiaq Chinese Japanese Leftist

D.H.Lawrencian background. It’s not a question of low self

esteem/inferiority complex, contrary to what my New York friends believe. We

can think we are great but we have to pretend we don’t think it.

Writing was all right for part of my cultural heritage – I had lots of

elders with the Great Alaskan Novel or Screenplay just waiting to be written or finished but in the back drawer. But they weren’t published and that

was part of the fear too: If I got great blurbs from the elite and my book

took off, it could hurt feelings and I would be violating the proper

hierarchy. I can’t even begin to tell you about the part of my heritage for

which writing novels is evil.

Second, short of an agent who had laid me off years before, I had zero

connections in the book or luminary world, though one cousin was a librarian

and one dead great uncle had written a book about socialism in Czech Republic. To try to find famous authors and get them to read my book and

then say it was good seemed as daunting as – well – getting published by a

NY press.

But then something amazing happened right when my novel was to be

sent to the printers: a highly respected anthropologist of the Arctic stayed

with my family in Nome and remembered my manuscript that she had read years

earlier. She had written a letter praising the novel and I had lost it

though I hadn’t lost fifty rejection letters from New York. But she had saved it and sent it and allowed my small publisher to put an excerpt on my cover. That was the first time I had even heard of “endorsement” for a book. I learned the word “blurb.” And this one worked magic.

For the first printing, that was the only blurb we had, but it got the book

into a hoity toity Seattle bookstore, with an author event there, too. This was

before any of the awards. With a marketing budget of zero, no distributor

(oops) and no publicity agent (too slimebag even if I could afford one), I was

learning about “cold calls” – how hideous they were and how unfit I

was to do them. The typical cold call: “Hi, I’m a writer with a new book you

might be interested in, a literary novel set in the Alaskan Arc-“

CLICK. (The sound of the bookstore person on the other end).

Next time (Feb. 16): how to get blurbs, what kind to get, and how they work for you. But don’t take my word for it.

~Lesley Thomas, author of Flight of the Goose: A Story of the Far North

http://www.lesleythomas.alaskawriters.com

Great to learn from your experience, Lesley, and I can’t wait for part II.

Oh my god — finally a post about my favorite pet peeve!

I’m not quite sure I believe that blurbs sell books, or at least, not significantly so. They seem, however, to be considered indispensible by industry insiders and readers alike. Without them, you’re either really famous or pathetic.

There’s a whole lexicon / hierarchy associated with blurbs: the “buddy blurb” (friend blurbing friends, to the point of incestousness); “blurbing down;” “blurbing up;” “lateral blurbing;” etc.

What does sell books? Timeliness? Quality writing? A clearly defined readership? A clever book cover or title? Name recognition? (Even different publishers come with different levels of prestige.)

As a writer, I mostly read blurbs to see who’s in bed with whom. I personally find it’s a lot harder to get a blurb / review from a respected publication than from an author. On the other hand, I have been extremely fortunate in approaching writers whose work I admire (and, whose work, I’d like to flatter myself, shares common ground with mine) and receiving generous blurbs. (In one case even after one of these writers had written an introduction to my new book, which I was unable to use.)

There’s amazing abuse of blurbs (I read about it in a funny NYTBR essay) by publishers who quote parts of a review out of context, or focus on the single positive statement in a review, or even edit a negative comment into a positive one: “mind-boggling” (nonsense).

In an era of flagging sales and soundbites and belief in “experts,” the blurb is a plain convention — and here to stay.

(How to tell the ones that are heartfelt from the ones that were written without having read the book, I can’t tell.)

My favorite blurb collection ever appeared as an ad the publisher took out for one of Norman Mailer’s books; it consisted of only the worst criticisms. Notoriety can be its own form of advertising!

I heard something similar to the Mailer anecdote, about an author who used bad reviews to peddle his book. Even bad publicity is good publicity, as they say.

Being more or less a blurb ignoramus, I had no idea there was a blurb lexicon. And naive little me – I hadn’t imagined someone would blurb a book without reading it.

Certainly name recognition sells books; hence the “value” of blurbs. What else sells books? Good, good question.

I’m not sure blurbs sell books, either, Michael, but my publisher is. I know writers who give blurbs indiscriminately, across the board to anyone who asks, without reading the book. I know writers who are stigmatized as “blurb whores” because of this. But publishers are convinced that an adulatory Big Name blurb or fullsome praise from a review in a Big Name publication will convince a reader to buy the one he or she is holding in their hands.

Maybe a blurb isn’t the only thing, but just the last thing, after their friend has told them they have to read this book, after the bookseller has forced the book into their hands, after the cover has seduced them with its wonderful art and great graphics, after they open the book to check to see the typeface is big enough for them to read without glasses, after the book passes the first page test, then, maybe then that blurb on the back cover is what finally convinces them to pull out their wallet.

So now that I’m catching up with the seemy underside of blurbs: Don’t blurb whores worry about damage to their own careers if they recommend a book their fans hate? Or a book that’s really not that good? Or are they so big that nothing can hurt them and they really don’t care?

When I see a big name praise a less known writer, my first thought usually is, “How did person A connect to person B?” — because even when the praise is warranted, there is some kind of networking or mutual backscratching connection.

But I’m not totally jaded. When I’m already interested in a book, as Dana suggested, the blurb does push the book up higher on my to-buy or to-read list. I just noticed that Juneau writer Stuart Cohen (The Army of the Republic) got a great blurb from Naomi Klein (author of Shock Doctrine and No Logo) and that grabbed my attention. As an activist, I think she must have pretty strongly about his book, which has a highly political plot, to provide that blurb.

Some reasons authors blurb without reading the book:

The author they are blurbing for is a friend.

Same above, plus they know if they blurb for him he’ll blurb for them.

An editor to whom they owe a favor calls it in for another author.

They figure it’s good advertising for their own books.

They can’t say no.

Okay, but why not read the book? I suppose, because as all of these reasons point out, it’s because reading takes time, and publishing is a business, and as a recent editorial pointed out, our culture seems to accept lying in the context of business. Is it morally rigid to expect that if someone praises a book, they’ve actually read it (or that they qualify their remarks if they haven’t)? We’d expect that of our friends. The public doesn’t know about the business. They think we writers are their friends, good and honest folk who’d never claim to have read a book we haven’t…

Oh, Deb. You sound so disillusioned. Welcome to the world of publishing. [Yes, I’m laughing, but not at you, with you.]

I’ve stood in bookstores watching people read the blurbs. It keeps the book in their hands that few seconds longer, and at this point I think publishers are desperate for any edge they can get.

This is the eternal curse of the YA writer, never quite losing the innocence, perpetual coming of age. I get it – we’re supposed to take blurbs as conventions, like Sarah’s letter endorsing the Texas gubentorial candidate, something authors sign their names to but don’t really write themselves based on the experience of reading the book. And I guess when you factor in the ghostwriting of books, it’s not a huge leap in the honesty arena.

I think another reason writers blurb without reading the book is that they really mean to but fall behind with their own work or new assignments that pile up and don’t want to disappoint the person who requested a blurb.

Like Dana, I see the blurb as one of many hurdles a book has to pass, or part of a funnel, if you will, at whose end stands a reader’s decision to buy a book. Or not. Cover, subject matter, timeliness, quality of writing, name recognition, and price all enter the equation. Fortunately for us, nobody knows exactly to what degree each of these influences the buyer’s decision. Otherwise, publishers would only contract for bestsellers and readers would only get to read those. It’s all part of the alchemy of books.

Questioning the “honesty” of blurbs is like questioning advertising in general, or people’s desire to look larger than they are. Some people do take blurb-writing seriously — unfortunately, it can be hard to tell them apart from the blurb whores.

On a different note, a blurb I get from an admired writer — a peer — can mean more than a review in a newspaper or even sales.

That’s the rub. We KNOW ads are manipulative. So blurbs are posers. But maybe a few are genuine. There’s no changing the reality of that.

As the funnel narrows, name recognition moves to the top. It all starts to sound sadly like the overall state of our economy. At some point the public (hopefully) figures out the trickle-down model (the funnel) is hugely flawed. There’s a movement to trickle-up, with its own inherent problems. The paradigm may indeed be shifting, at last, before our eyes. A post on this is simmering.