Photo caption: Taras Shevchenko (1814-1861), Ukraine’s beloved poet, playwright, and painter is honored in this bronze statue installed in 1960 in Washington, D.C. and dedicated by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Its inscription says it is “Dedicated to the Liberation, Freedom, and Independence of All Captive Nations.” Shevchenko spent many years imprisoned for his pro-Ukrainian sovereignty activities in czarist Russia. The statue is maintained by the U.S National Park Service. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Library of Congress.)

PART ONE

Ukrainians are being praised for their bravery, courage, and resistance against Russian aggression. It has been unbelievable to see the news about Ukraine’s fight for freedom, how they have managed to combine military force with extraordinary inner strength to defend and hold on to their democratic and sovereign homeland.

The immediate response to Putin’s assault from Ukrainian writers and poets, and from those who stand in fierce solidarity with them, has also been remarkable.

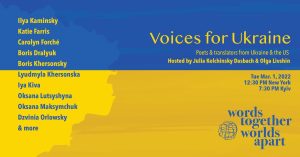

Less than a week after Vladimir Putin’s “special military operation” began, I received word in the comfort, warmth, and security of my Anchorage home that my friend and former Alaskan colleague, Olga Livshin was helping organize a Facebook live stream poetry event called Voices for Ukraine.

Olga Livshin, poet, writer, translator, and teacher now resides in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. She was born in Odesa, the daughter of a Russian-Jewish journalist. Olga emigrated to the U.S. with her family when she was fourteen. We first met at UAA where we both worked and shared adjacent offices, she as the Russian language professor, and me, as the program coordinator of UAA’s low-residency MFA program.

Poet Julia Kolchinksy Dasbach who earned her Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania, co-organized and co-hosted Voices for Ukraine. Julia emigrated from Ukraine to the U.S. as a Jewish refugee at age six.

The 2.5-hour Voices for Ukraine program on March 1st which sprang together with hardly any advance notice, instantly drew an audience of 860 or more from around the world—writers, translators, Ukrainians, plus regular readers, and people from as far away as Bangladesh who have nothing to do with literary circles.

Olga and Julia described it as a “transatlantic, trilingual (Ukrainian, Russian, English) virtual event in the middle of war and displacement.”

Voices for Ukraine was unlike any live Facebook event I have attended. While listening to this spontaneous combustion of creativity, the firepower of international camaraderie being publicly expressed for Ukraine, I kept asking myself, “Is this real? Are Russia and Ukraine really in a war?”

As a writer, this part of the world—Ukraine, Russia, Poland, and the Baltics—has been a personal area of focus for several decades. I lived solo in Krakow, Poland for most of 2014, and from my rented flat in the Kazimierz district, continued working on the manuscript for my book. I first went to Russia in 1990, and most recently, have made four trips to the country since 2003. In January 2020 I flew nonstop from Los Angeles to Moscow on Aeroflot, right before the killer virus disrupted everything. Returning to Russia anytime soon will be impossible.

On Voices for Ukraine, an array of powerful voices united to recite their poems, including Boris Khersonsky and his wife Lyudmila Khersonska who joined in live from Odesa. (Khersonsky has 36,000 Facebook followers, but I did not know his work until I listened in.)

“This was such a space of support and solidarity, so many tears and such positive energy, such hope in the face of atrocity and catastrophe,” co-organizer Julia said in an email.

One of the featured poets, Iya Kiva, had just been fighting for the last two days, and posted on FB that this was the first night she had slept in her apartment. Another poet, Lyuba Yakimchuk, had been gathering medical supplies and her husband was driving them to hospitals in Kyiv and Kharkiv, across dangerous roads being bombed and patrolled by Russian troops.

“And these poets, they took time away from much more urgent work,” Julia said, “to be with us, to read poems, because poetry is its own urgency.”

President Volodomyr Zelensky, as of this writing, remains protected within the ancient and beautiful fortress of Kyiv. There is something special about Zelensky’s voice which obviously relates to his former life as a professional actor. He is someone who carefully considers words he makes, and words he hears. I pay close attention to his verbal mannerisms, his tone, how he sounds in translation. I do not yet hear any double-speak pouring from his lips.

PART TWO

What happens, during tragic and dangerous times such as these when poets rush in?

Do missiles suddenly stop flying? Do Russian soldiers abandon their convoy and park the tanks, and peacefully walk away? Do politicians (from everywhere) who blindly tow party lines quit promulgating lies and supporting propaganda? Do authoritarian rulers squirm, break out in a sweat, reverse course, and back off in order to dismantle their global reputations as possible war criminals?

Of course not. I ask only for rhetorical effect.

CNN recently interviewed a Moscow journalist who worked at the last independent television channel, TV Rain, now shut down. The anchor and news director explained that Russian people don’t want to be isolated from traveling and communicating with the rest of the world. The cultural interconnectivity between Russia and other countries has been very strong among the younger generations.

Her words made me shudder: This is the end of the Russia we had known.

“Putin has destroyed everything free and independent in the federation. We haven’t seen anything like this.”

What kind of 21st Century Russia does Putin want? What is the world in for?

On my winter trip to Moscow in 2020 to see my long-time Russian friends, the city looked resplendent, and more prosperous than I had ever seen it. We took pleasant but cold evening walks along the Moskva River lined with shops playing Western music, and with sparkling strands of colored lights adorning several miles of riverfront. Every day, my nine-year old surrogate niece and I worked together on her homework practicing English. She studies at a private language school in addition to attending her regular public school full-time.

Whenever I speak a few words in Russian, the sounds and rhythms strike some pleasure center in my heart. And then I come home to Alaska, leave my notebook on the shelf, and quickly forget all the new words I learned.

Putin continues to squeeze freedoms, making it illegal for Russians to publicly criticize the government’s invasion. Over 4,300 more protestors on the streets of Russia were detained; an estimated 1,700 of them were automatically thrown into jails and prisons or hit with large financial penalties. On state-controlled media, Putin angrily calls America and the West the “empire of lies.” He alleges that the Russian military is not killing Ukrainian civilians.

One of my Russian acquaintances, a professional filmmaker and cinematographer, has left his home in Moscow and is, at this moment, on his way with his wife and children, driving to Georgia to escape the chaos.

This pattern of migration sounds historically familiar. After the Bolsheviks seized control during the Revolution, many educated Russians from the cultural elite, the intelligentsia, departed in the 1920s and early 1930s, choosing instead to live as emigres in Paris, where many continued to write and publish poetry, prose, theological and philosophical works.

Several years ago, Olga Livshin and I collaborated to design and co-teach a 49 Writers seminar on Anna Akhmatova, one of the greatest poets of the Soviet era who briefly traveled to Paris as a young woman, but who remained inside the Soviet Union. Akhmatova lived through the bloodshed, the assassination of her husband, the imprisonment of her son, and the calamities of World War II, including the horrendous Nazi siege of Leningrad, as recalled in her famous verse, “Poem without a Hero.”

A vast land of extreme contrasts, paradoxes, and contradictions, Russia’s long history is an anguished and glorified one. A continuous cycle and battle between repression and liberalism on an unfathomable scale. Russia is at once a cold cellar and a warm hearth.

And now Ukraine…

PART THREE

My first, most vivid impressions of Russia date back to age 14 in my birth city of Pittsburgh when I happened by chance to see the much-acclaimed film Doctor Zhivago in matinee reruns.

I grew up mainly viewing Russia and the USSR as the monstrous enemy of freedom-loving America. The country was full of conformists and automatons who, out of fear, had to be obedient and march lock step under their communist leadership.

As a kid, I could absorb very little about Doctor Zhivago’s political realities, the reasons for the chaos and violence, i.e., the shootings between Reds and Whites, whoever they were, and why so many nice people were freezing to death, going hungry, and abandoning all their belongings, fleeing to any place where small personal freedoms could be found.

Maybe in my young mind, as I watched those haunting images and as I listened to the unforgettable balalaika soundtrack in Doctor Zhivago, I started to subconsciously absorb some understanding of what Russianness was, besides the standard communist stereotypes I was exposed to.

Over and over again, as an American, as someone with Polish and Lithuanian ancestry, and as a writer, I have been determined to scratch below the surface, to make attempts to understand something more meaningful and experiential about Eastern Europe and Russia, in what truths are known beyond economic analysis.

By the time I got to Alaska in 1978 and lived for a time in Sitka (New Archangelesk) and on the Kenai Peninsula where there are Russian communities of Old Believers, my interest in Russian history and culture expanded.

I have watched and re-watched Doctor Zhivago many more times. I believed there was such a thing as Russianness, and that it must have something to do with the symbolically powerful images British film director, David Lean, masterfully created in his interpretation. What lodged in my imagination were the panoramic shots of the snow-covered Urals; whistling trains; women in furs; clanking trollies similar to the streetcars I always rode in my Pittsburgh childhood.

From the film, I vividly remembered the ominous looking steppe, the fields of sunflowers, how the remaining leaves from golden birch trees scattered and fluttered across the wintry ground. And that chilling line from the movie spoken by a revolutionary: “The personal is dead in Russia” has never left me.

The leading man, physician-poet, Yurii Andreievich, played by Omar Shariff, was not any kind of an American action hero, wielding weapons, and leaping from tall buildings.

In one of the scenes I could never forget, Yurii stayed up all night in a freezing room in rural Russia, hovered over a small table, writing poems while his mistress slept. He wore threadbare gloves and wrote with the light of only a single candle. The wolves howled outside, a metaphor for the ravages yet to come. The candle was a direct reference to Pasternak’s poem, “Winter Night,” part of a cycle of poems he included as a kind of appendix to his novel. The line from “Winter Night” is: “A candle burned on the table / A candle burned.”

Yurii, this weak, passive, and distracted man, as some believed, did not define himself according to external political structures, dogma, or party labels. He maintained his “secret” interiority and personhood. Manuscripts don’t burn, as Bulgakov said.

Through my travels and readings, I learned about the values and temperaments of everyday Russians, their stories, folklores, myths, and symbols that spoke more directly to whatever this idea of Russianness was, outside the assessments of the Kremlin, European economic councils, and American think tanks. A more idealized, less morally and politically corrupt Russia, in other words.

In my mind, it had something to do with a whole whirl of images that raised a different kind of historical consciousness: spending time breaking bread with strangers around a hand-hewn table; walking through forests; journeying as a pilgrim to visit a staretz for spiritual wisdom; steaming in the banya; riding horses and sleighs; foraging for mushrooms; ballet and Tchaikovsky; growing vegetable gardens at dachas; making cabbage soup, blini, and pelmeni; sewing and embroidery; selling a sack of potatoes on a roadside stand; village folk dancing and singing in the villages of Chuvashia or Novgorod.

PART FOUR

Voices for Ukraine reminded me that I should be reading more contemporary Ukrainian poets. I do own one book by Sirhiy Zhadan, poet and novelist from Kharkiv. My only experience in Ukraine was spending an entire night trying to sleep in the Kyiv airport when my flight to Krakow was canceled.

I finally got around to reading Doctor Zhivago in 2003 when I took my first trip to St. Petersburg for the 300th anniversary of its founding by Peter the Great. (The novel was banned in Russia until 1988.)

Most writers know the story of Pasternak’s last few years, but as we witness what’s happening today under Putinism—his vehement intolerance for even a shred of dissent or free expression—the Pasternak affair bears repeating.

One of the greats of Russian poetry, Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, but in a hail of criticisms by Soviet authorities, capitulated, and declined acceptance of humanity’s most prestigious literary award.

In 1957, after the preeminent Russia literary journal, Novyi mir, refused to serialize any part of Doctor Zhivago. The manuscript for Doctor Zhivago had to be smuggled out of the Soviet Union and published first in Italy. An English translation appeared in late summer 1958, and on October 23, 1958, the Nobel Prize was announced in honor of Pasternak’s lifetime achievement as a scholar, translator, poet, and prose writer.

Four days later, Boris Leonidovich was expelled from the Union of Soviet Writers, the organization established in 1934 by the government and to which all professional writers were obliged to belong if they hoped to earn any kind of frugal living as translators, writers, or editors.

Internally, the Soviet press viciously condemned the writer. During the scandal, the Authorities labeled his one-and-only novel as “squalid.” An international furor quickly erupted over his harsh treatment.

The beleaguered poet, under severe pressure, issued a lukewarm public apology for having written the unacceptable Doctor Zhivago.

Pasternak’s novel, which he considered his best work, never mentions Lenin nor Stalin, nor does it celebrate the Russian Revolution. It does not reaffirm or comment on any communist doctrines or theories. What it does do is illuminate the human condition.

From 1958 until 1960, the poet, spiritual writer and Trappist monk, Thomas Merton, exchanged several letters and books with Pasternak from his Cistercian monastery near Bardstown, Kentucky. After the writers’ union expelled Pasternak, Merton got wind of all the controversy and strongly defended him. (All of Merton’s mail was censored by his religious superiors, but somehow, he was granted special permission to send letters to a fellow poet in the nefarious Soviet Union!) The renowned Catholic monk typed and mailed a letter to the Soviet Writers’ Union. Not long after, Merton wrote and published a brilliant essay of over 30 pages on Pasternak’s genius. On the pages of his journal, Merton asked: “How else shall I study Boris Pasternak, whose central idea is the sacredness of life?”

Concealing truths about dark realities is something the Soviet government did exceedingly well throughout the twentieth century, especially during the Great Terror.

The biggest lies Stalin and his associates told about Ukraine was that there was no forced famine, no Holodomor in 1932-33 when, in fact, an estimated 10 million peasants died in Ukraine, Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan, including three million children who died of hunger, in his campaign to crush and liquidate the peasantry and kulaks in the name of farm collectivization and de-nationalization. The truth about the loss of life was not fully disclosed until secret files were opened during the Gorbachev era. (The historian Robert Conquest in his book, Harvest of Sorrow, estimates that a total of 11 million innocents died in the Soviet terrors between 1930-1937.)

As a young but internationally known and important Soviet poet in the early 1960s, Yevgeny Yevushenko (1932-2017), spoke assertively for the need to substitute falsehoods for truth, and for poets to have more artistic autonomy. Born in Winter Station near Lake Baikal in Siberia, I once heard Yevtushenko give a poetry reading at Eckerd College in Florida. In his 80s, he was living in, of all places—Oklahoma. Yevtushenko stated that it was the early generation of poetry post-Stalin, in his generation, that created the “cradle of glasnost.” The zestful, charismatic Yevtushenko had paid several visits to Alaska over the years, referring to Alaska and Russia as “un-justly divided twins.”

During glasnost and perestroika, a grassroots euphoria swept through Alaska, and back then, in the early 1990s, I was a part of it.

Part of my job was to organize several Alaska State Chamber of Commerce trade missions in the Russian Far East to promote business cooperation. I studied Russian at UAA, hired a private Russian language tutor, hosted an exchange student from Magadan in our home, and traveled to Irkutsk, Vladivostok, Khabarovsk, Chukotka, Moscow, and to Magadan. (The port city of Magadan shares a subarctic climate with Anchorage and was officially designated as our “Sister City.”)

In the years before Putin came to power, optimistic Alaskans—and not the Washington, D.C. policymakers—seemed more ready and psychologically equipped to help build the New Russia. Various indigenous peoples could prove they shared common ancestors and bloodlines with Russians across the Bering Sea, in Yakutia, and Chukotka.

Given the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it seems incredible now that those cultural efforts and ties built in the 1990s between the U.S. and Russia might be buried until the next thaw.

THIS BLOG’S FINAL CURTAIN

Putin’s imperial gamble, his unconscionable invasion of Ukraine, is tragic and hard to stomach.

It’s as if the historical clock has been smashed to bits, and we are plunged backward into a warped recidivism, to a divisive and frightening world order full of threats and fears about nuclear weapons, and malicious psychological warfare resembling Cold War 2.

I think back to a September day in 1991, when Russia was reforming from deception and economic disaster to more truth and reconciliation. As staff to a delegation of high-level Alaska mining officials, I was on a second trip to the Russian Far East. Our business group was hosted in Magadan by the state-owned Russian energy company. Magadan, on the Sea of Okhotsk, was an administrative center for mining operations but it had retained a gruesome reputation with its involvement in the forced labor camp system during Stalin’s time.

Magadan looked dilapidated, run down, and economically forgotten by Moscow. I remember seeing bathroom plumbing held together with duct tape, and visiting apartments where families lived completely crammed into tiny spaces in ugly concrete buildings where the central government controlled the dates and times when families could turn on their hot water.

Our meetings took place at a retreat complex reserved for high-ranking managers and engineers and their families out in the country, about 30 kilometers distant from Magadan proper.

I walked around the drab, 1950s buildings and performed my patriotic duties–I passed out candies and trinkets of Alaska flag pins to any boys or girls I might see.

A girl of about age nine confidently stepped towards me and said hello in polite Russian. Nadia was dressed in a red skirt, baggy tights, and wore a yellow satin bow in her hair almost as big as her head. Before the children had darted for the candy, they had been occupied playing with glass bottles and cans. Nearby, I spotted a long wooden panel painted with a portrait of Lenin. In the display of public art, Lenin was surrounded with members of the young communist league, each of them smiling and saluting to the hammer and sickle of the Soviet flag.

After Nadia put the bubble gum in her pocket, she turned to me, assumed more of an erect posture, folded her hands, and began reciting a Pushkin poem in Russian that I could only half-guess had to do with autumn and falling leaves.

I often remember this little innocent with her wide smile, the one who freely recited some verses to a stranger and foreigner from the decadent West. In that frozen and tender moment of time in Magadan, it was joyful to longer be “of the enemy.”

No child since Nadia has ever said thank you with such an unusual and unpredictable gesture. I still picture her in her proud and formal stance reciting Pushkin without hesitation or stumbling. How very Russian all of it was then.

Kathleen Tarr, Anchorage, is the author of the memoir, We Are All Poets Here. She is a founding member of 49 Writers, a member of the Alaska Historical Society, and a former board member of the Alaska Humanities Forum. As a Thomas Merton scholar, Kathleen frequently speaks and teaches about his work and legacy, and currently serves on the national board of the International Thomas Merton Society, based in Louisville, KY. She earned her MFA in creative nonfiction from the University of Pittsburgh. Reach her at: ktarralaska@gmail.com and at kathleenwtarr.com.

Thank you so much for this Kathleen,

As a 49 writers board member and granddaughter of Latvian immigrants, I appreciate these reminders of the ambitious efforts to strengthen close connections between Alaskans and Russians in the sad Soviet times. Perhaps we can reach out to Ukrainian writers as the current diaspora settles in. -Katie Bausler

Thank you for sharing these reflections, Kathleen! Your statement in Part Two captures Russia particularly well, I think, and I hope more people in our country (the US) will reflect on such insights, now and in the future: “A vast land of extreme contrasts, paradoxes, and contradictions, Russia’s long history is an anguished and glorified one. A continuous cycle and battle between repression and liberalism on an unfathomable scale. Russia is at once a cold cellar and a warm hearth.”

Hi, Carolyn! Thank you so much for taking a rather long time-out, to read my blog/essay. I know you share many of the same impressions and personal reflections about Russia. The Russian-Ukrainian “special military operation” or “war” is causing the whole world to think about the future and what really matters.

Thank you, Katie! Sad Soviet Times seem to be recurring, don’t they? Alaska has always been a unique position to keep people-to-people efforts alive between Russia and the US. Writers and poets in both countries have obligations to tell the truth and to provide hope. Thank you so much for reading the post. Slava Latvia, Ukraine, Poland and Lithuania!