Today I did an itty-bitty trail run following strict doctor’s orders: fifteen minutes maximum; alternate running with walking; stop at the faintest niggle of discomfort. All went well and I’m hoping that after I manage three of these in a row, pain-free, I’ll slowly return to regular running following a six-week prescribed break. If not, I’ll deal with it.

It occurs to me that I didn’t mope, worry and catastrophize half as much about this injury as I did about my previous ones, including a bizarre leg pain I had a year ago (not caused by running).

My understanding of injuries had changed.

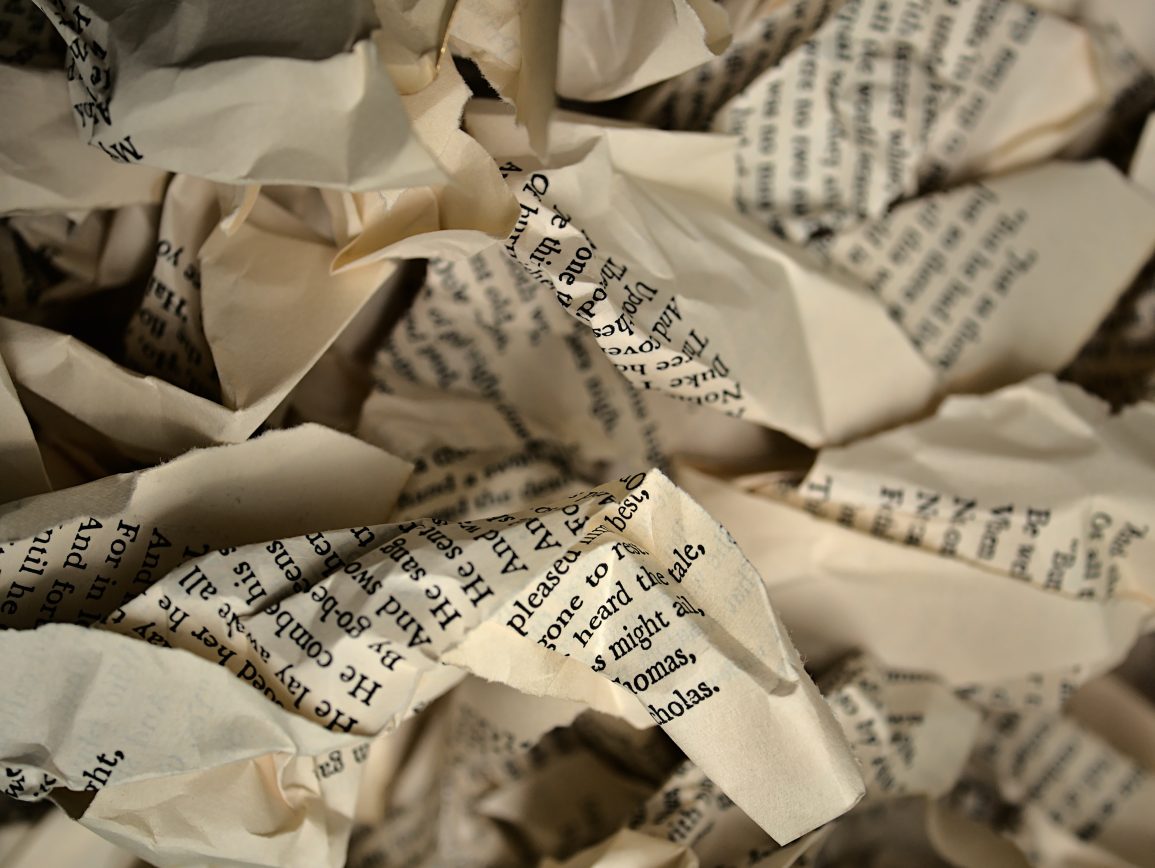

This epiphany hit me alongside a second one: Recently, for the first time, I threw away hundreds of new novel pages without sliding into a serious depression.

The novel hiccup happened in November, when I set aside a project that had reached 65,000 words. That’s at least two-thirds of a book. I’d been working on it well over a year. The decision to set the novel aside took only a couple of days.

I’d been under some stress for unrelated reasons when I made this decision, so I expected the cumulative toll to flatten me. Certainly, it was a bad week. I wrote angsty emails. I made cryptic marks in my daybook: “(title of book) feels broken.” “D. Day.” “Malaise.”

After three more days of self-pity and indecision, I stayed up until 2 am, overindulging. I’m not looking for approval, but there are times when our Hemingway sides surface, and for me, it’s when I sense a major writing project has imploded.

But while I was granting myself permission to enjoy gin and tortilla chips in deliberate excess, I was also taking notes for a new novel—the same one that has occupied me happily ever since.

In every writer’s life, there will be more insults and injuries than we dare imagine. Negative notes from first readers. Snarky comments from family and friends. Editorial letters that are mostly red ink. Rejections. Bad or incompetent reviews. Disappointing sales. Snubs and barbs and heart-breaking realizations of all kinds.

In some ways, I’ve found the writer’s life getting harder as I age. I can’t sit for hours, due to a chronic back issue. I’ve grown wary of the business side of publishing, though I also make a real effort not to let that wariness harden into cynicism.

But here’s one thing I never expected: bouncing back from disappointment and perceived failure has gotten much, much easier.

About fifteen years ago, the first time I set-aside a full manuscript that my first agent disliked, I felt like the rug had been pulled out from me—for two years.

Two years! And possibly longer than that, because that failure haunted me even after I wrote and published the following book.

Later failures knocked me over for months at a time.

This latest one, by comparison, didn’t even last to the weekend. I’d drowned my sorrows but there was still gin left in the bottle. (Alas, the tortilla chips were gone.)

In the hope of helping others who agree that bad news and writerly melancholia are inevitable, I want to explore why the most painful part of my injury/rebound cycle may have shortened—and suggest some tips to apply to your own rebounds.

Experience: The more pages I’ve written, the less the current ones count, ratio-wise. My latest “failed” manuscript represents less than one-twentieth of my fiction output. It feels like even less than that.

Can you focus on greater productivity, in order to tolerate the scrapped pages and down-times with less suffering? See, the oft-quoted “parable of the pots,” from the classic book, Art & Fear.

A learning mindset: With this latest project, I was consciously trying out some new techniques in a new genre. Failing to finish or sell the book doesn’t mean I didn’t learn a ton—and enjoy the process.

Can you remind yourself of the benefits of writing, regardless of outcome? Can you applaud yourself for those times you manage to savor process over product?

Immense faith in revision: I already have one published novel, Annie and the Wolves, that I declared “D.O.A.,” gave up on entirely, and then picked up and radically revised a half-decade later. Now it’s extremely easy for me to imagine I may pick up this latest set-aside manuscript—whether in six months or six years—and work on it again.

Can you become a revision expert, confident that you can rework old material into new shapes, and always looking for new tools and strategies for doing so? Can you keep the door open to returning to a manuscript later, but without obsessing, so you can get a true mental break from it?

A new idea in the wings: This may be the key reason I rebounded quickly. I’d had a new idea whispering in my ear for months. I resisted fully indulging the charming interloper until my current project was set aside, but I made a place for her. I bought a few key books. I bookmarked websites. In a sense, I was gathering tinder all along. When I needed to light a new fire just a few days after the last one went out, it was easy. WHOOSH.

Do you keep an idea file, with loosely jotted notes or quick-writes (scenes, character studies) related to potential new projects? Can you cultivate multiple sources of inspiration without getting distracted?

I started out this blog post talking about a running injury, and that’s because I see a key parallel. When it comes to athletic injuries, I’ve finally grown to accept them. I’m working on seeking help more quickly and following treatment advice more closely. Now l cross-train, so healing doesn’t have to mean complete inactivity.

I’m also learning to notice my own patterns, like how long I take to heal. I endeavor to accept the process and, whenever possible, minimize “worst case scenario” thinking.

Consider this as a writing prompt:

What are your best, healthiest ways to deal with your bad news or downtimes as a writer? How many days should you allow yourself to a) mope; b) not write; c) assume the muse has flown and will never return? Can you let yourself take a full break without fear or shame, and recognize the right time to move on? When writing isn’t going well, can you cross-train in another way, e.g. by giving yourself a “vacation” to focus on reading with a particular purpose in mind?

Also, think about preparing ahead of time:

Whatever hits you hardest—unsupportive comments, a bad review, critical notes from an editor, the decision to quit a project, or in the case of memoirists, backlash from those you’ve chosen to write about—do you have a remedy ready? Consider creating an “in case of emergency, break glass” writer’s file. Save inspiring articles or quotes, biographical tidbits about other writers’ hardships, beloved writers’ bad reviews, or essays about dealing with family criticism, for example.

Know thyself, and know the hard days are coming, but you’ll get through them.

Hopefully, you’ll be writing and back on the proverbial trail in no time.

Andromeda Romano-Lax is a book coach and the author of five novels including Annie and the Wolves (available in paperback), chosen by Library Journal as a Best Book of the Year and by Booklist as a Top Ten Historical Book of the Year. In 2022, she plans to finish a new novel draft and compete in a half-Ironman. Follow her at @romanolax or visit her at www.romanolax.com.

Thanks, Andromeda. Words I needed to hear at just this particular moment.

Glad to hear that, Anne!