In 2015, JT Torres was teaching developmental writing at the University of Alaska, Anchorage. The prior two years, he had lived in Colorado and Georgia alone while his girlfriend finished nursing school in Florida. Torres’ university contract was scheduled to end in May of that year. His lover had committed to serve Alaska Regional Hospital for two more. He probably would have stayed in Alaska if he hadn’t run into Professor Jill Flanders Crosby, Chair of the University Dance Program. She changed his life.

Professor Crosby had just read Torres’ MFA thesis, which included “a novel about [his] grandmother’s life in Cuba—a life filled with spirits and ambiguous religious convictions.” (J.T. Torres: Performance Research, January 7, 2015 49 Writer’s Blog Post).

When they first met, the professor told Torres, “You are exactly whom I’ve been looking for.” (1/7 Blog Post).

Torres remembers first meeting the professor in her office, “The snow outside her window, illuminated blue by the brief couple hours of winter daylight, filled her office with a dreamlike aura. Books spilled from her floor to ceiling shelves. Papers piled on the floor. I had to move a VCR from the chair in order to sit. She spoke like she’d known me for years, like she’d been looking precisely for me.” “Want to go to Cuba?” she asked. He did. [1/7 Blog Post).

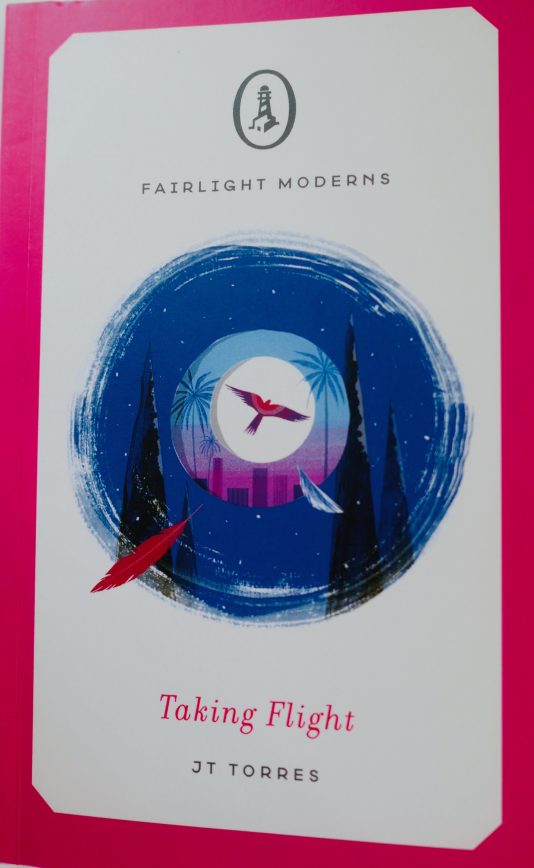

Six years after that first meeting with Professor Crosby, the two of them published “Situated Narratives and Sacred Dance: Performing the Entangled Histories of Cuba and West Africa.” This month, Torres’ debuts the fiction work, “Taking Flight,” which was published in Great Britain by Fairlight Moderns. It will be available in America in October of this year.

A copy of “Taking Flight” showed up in my Alaskan mailbox last week. With it, Fairlight Moderns Press provided a very good summary of the book:

When Tito is a child, his grandmother teaches him how to weave magic around the ones you love in order to keep them close. She is the master and he is the pupil, exasperating Tito’s put-upon mother who, although exhausted from working long hours, is usually the focus of their mischief. As Tito grows older and his grandmother’s mind becomes less sound, their games take a dangerous turn. They both struggle with a particular spell, one that creates an illusion of illness to draw in love. But as the lines between magic and childish tales blur, so too do those between fantasy and reality.

In this beautifully told drama of the bond between grandson and grandmother, J. T. Torres delicately explores the complexities of family bonds – in which love is need, and need becomes manipulation, along with the pain and difficulties of dementia and mental ill health.

The Alaska writer, and professor at UAA, Don Reardon wrote that “Taking Flight stirs the heart with the revelation that when it comes to the greatest illusions in life, the real magic exists only because of love.” UAA Professor Jill Flanders Crosby wrote that “JT Torres’ story is a masterful work written in the style of magic realism that slowly peels apart the passing down of the “immigrant experience” from one generation to the next.”

Taking Flight is written well. In it, Torres shares the relationship of his main character “Tito,” his sister “Titi” and Nana, his Cuban grandmother. Once, when he was very young, the grandmother told Tito how he and his sister got their Cuban names. “My parents ran a chicken farm with some friends in Cuba. We called for the chickens by yelling ‘Titi, Titi.’ Tito was what we called the rooster. You are supposed to be the leader, but your mother loves Titi more than anyone else.” Stories like these gave Nana the opportunity to take control of her grandson. She used it to create an illusionist.

Tito used ketchup and severed clothing to mock death. Later, he tried to convince his parents that he was a dog. One night, his father found him in a closet at 10 p.m. polishing his shoes. He asked Tito’s mom what was going on. She assured him that “He’s not a dog any more…[h]e’s a maid.” All through high school, Tito would come home from school each day to strip out of the “parakeet-colored windbreaker…hiding [his] vanishing body.” These and other passages convince the reader that Tito was no longer using performance to create illusion. He believed that what others might consider an illusion was real.

Torres ends the novelette with a story of Tito and Nana searching for birds in a Florida alligator park. In a place where no one expects to find birds, Nana and Tito watch the sky fill with them, including “three purple-tipped nightingales.” Nana had earlier told Tito about a Cuban man who lived alone in a cave after his family was destroyed by a hurricane. Hearing nightingales sing outside his cave, the man stepped outside and was transformed into one. From then on, he flew above Cuba, sharing songs of youth and joy.

Like most Americans, I was raised to search for reality and avoid falling for illusions. Torres works hard to convince us of the possible positive power of well-intended illusions.

.