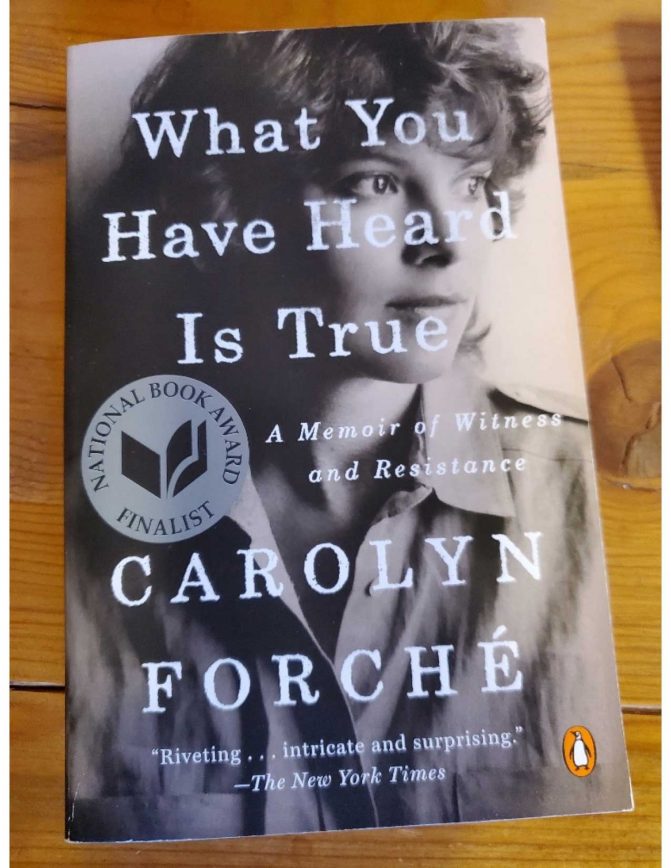

The poet and memoirist Carolyn Forché joined the book club in the Copper Valley via Zoom on January 30 to talk about What You Have Heard is True, her experiences in El Salvador careening toward its 12 years of civil war. Her grace in spending time with us, and what she shared, will be with us for a long time. Her memoir is starkly real, far beyond experience for me (and I am presuming others) and delivered straight to the heart with the leaps and associations of poetry. She told us she rewrote the manuscript four times. The final draft is worthy of her Salvadoran mentors’ intentions: that only a poet could see and convey what was happening to their country.

What we call magical realism is enabled by an account wherein the reality described is so unimaginable that the actually impossible gets gathered into the mind alongside all other details, to be wondered at later or expunged from memory, wherever it is we exile what we are unable to consider from a landscape too strange. That air of Márquez, turning to flowers. Those white-billowing European ships on the horizon of the new world, invisible to eyes without their future.

At the end of What You Have Heard is True, author Carolyn Forché and loved ones of El Salvadoran activist and peacemaker Leonel Gómez Vides carry his ashes up the slope of the volcano to be scattered. They climb through saplings growing up in a giant crater dug in the civil war, “when the blast was heard in the surrounding hills and seen as black smoke rising to the clouds from where it came – trees yanked out by their roots, boulders sprayed into the air, and earth blasted away, taken up, never to rain back down. Nothing was ever found of that earth again. It remained in the clouds.”

The earth is vaporized – literally true – but more. Forché takes us through days experienced by her 27-year-old self in the days before the war, a limited point of view that does not speculate backwards or look forward. She takes readers into a fearful, unimagined and unimaginable landscape of torture, death squads, political imprisonment in boxes where men were crippled and went mad. Leonel’s “reverse Peace Corps” education for Forché continually exhorts her young self to “see,” “look deeper,” and someday write, as a poet, what she has seen.

Forché’s young self resists, but she does not leave the task she doesn’t fully understand. She looks at brutality and hopelessness a young North American has no equipment to perceive. She tells Leonel he needs a journalist, not a poet, to do this work of witnessing and reporting. There is a cultural mismatch here between the esteem for poets in Latin America and a common disregard for poetry in the United States, as mere decorated language. “It is difficult to get the news from poems,” as poet William Carlos Williams told us, maybe because we think there isn’t any. Leonel tells her never mind; only a poet can do this work.

Forché’s unflinching, fearful views come to us in prose 40 years after their facts, fulfilling her promise to Leonel Gómez and the martyred Archbishop Oscar Romero. In the interim, she has included her El Salvadoran experiences and insights in multiple books of masterful poems, and in her deep commitment to human rights work around the world. She is called, and calls herself, “a poet of witness.”

Poet’s craft blooms in Forché’s prose, as she lays the monstrous testimony of a young man from the death squad against his childlike nature, then the physical threat of a young man robbed of his humanity against his role as chess tutor to her precious and vulnerable child. Descriptions are powerful and spare. Justice is deferred until it feels beyond hope. When it is denied, as for “Alex” who has come to tell the United States what he has seen, and to describe our culpability in the death squads, it spears the reader’s ambient, ignorant faith. As Forché and Alex have learned, what can happen in one place can happen in all places. Alex believes this because a poet has said it, and because he will live it. Can we learn this? Can a poet teach us this, beyond what a journalist can do?

The poems from her new collection In the Lateness of the World, like the prose memoir published in the same year, leave processing of meaning beyond their moments to the reader. Forché writes about others, dedicates her poems to others, but the dedications and context are not overt. “See this,” she is telling us, “look again,” through impacts in the poet, juxtapositions of detail. Look at the luxury of a hotel against the corpse of floating child (“The Boatman”). Look at a child in a dream, walking over bones “whose flesh / was lifted by zopilotes into heaven” (“The Ghost of Heaven”). Context can be found with a Syrian taxi driver, the experiences of Forché with Leonel. But spare of these, in doing the work of a reader, both poems and prose are deeply radical and humanistic without being ideological. They live underneath the details of what we believe, in the miracle birth of human language.

In “The Lightkeeper,” there is a night ocean without ships, “Foghorns calling into walled cloud … That after death it would be as it was before we were born. Nothing / to be afraid. Nothing but happiness as unbearable as the dread from which it comes.” Think of loss and the bravery that can only come after: to go “toward the light always, be without ships.”

Fog, cloud, disappearances are of the mind and of the world. They suggest the impossibility of witnessing: “In this archipelago of thought a fog descends, horns of ships to unseen / ships…”. But what can’t be known or seen now is there, too, as ghost or promise: “…where you have gone and come back, light, no longer tethered / to your own past, and were it not for the weather of trance, of haze and / murk, you could see / everything at once: all the islands, every moment you have lived or place / you have been, without confusion or bafflement, and you would be one person. You would / be one person again” (“Toward the End”).

There are many kinds of bearing witness. Maybe only a poet can show us the earth gone to clouds. And what it has to do with us.

-Mary Odden

Nelchina