So, yesterday I was writing this sentence, and the fancy grammar-check tool in my laptop caught me failing to practice what we preach in “flash” writing workshops: ie. writing precisely and economically. Our motto is “A Few Good Words”.

The sentence: He reverts back to his usual snarly tone.

It’s not the worst sentence I’ve ever written, but there’s room for improvement, mainly, the removal of that extra word, back. There’s no need for that.

“Revert” means: to return to a previous state, practice, or topic.

He reverts to his usual snarly tone. Period. It’s not only adequate, but tighter. Why didn’t I see that?

Here’s another one: Pamela cradled a roosterfish in her arms.

Duh. “To cradle” means to hold gently and protectively:

This is what I should have written: Pamela cradled a roosterfish. Period.

But all that raises a question: why try to write flash prose in the first place if a person only wants to write ordinary-length short stories or personal essays, or even novels?

Fair enough.

The answer is, because studying the rigid requirements of extremely short prose helps us clean up ALL our writing. It trains us to be more aware of all the choices we make every time we write a sentence. That’s an essential skill for any serious writer.

Neither of the two examples above is from flash writing. The first is from a novel I’m working on, and the second is from a long essay for an outdoor magazine where I contribute occasionally.

When I started writing in the late 1980s, I was terribly wordy. I wrote the way I talk, and anyone who knows me knows I’m a very blabby guy. (Take this class and find out.) That can be fun in social circumstances with plenty of laughter and maybe a few adult drinks. But dumping excess and empty verbiage on a screening reader at a magazine, publishing house, or a literary agency, is an almost sure way to get them to put your manuscript down. Of course, any good editor could cut much of that excessive stuff, if they had the time or inclination. But they have neither. Not anymore, thanks to an endless tsunami of electronic submissions today.

As a new writer, I was lucky to run into a generous southern gentleman editor back in 1991 when I submitted a story to the Crescent Review out of South Carolina. Guy Nancekeville sent me his edits of my story, which he did in pencil on my manuscript. Yes, this was so long ago we mailed paper copies back and forth in envelopes with colorful, little stamps on them. Remember stamps? Ink on paper? Saber-tooth tigers?

In the letter he sent with my manuscript, he wrote this.

“I am going to go through your story and cut (the unneeded words). I’ll do this fast, because I’m running out of time. I will take out too many, because the way to straighten a stick is to bend it too far in the other direction. I’m not trying to boil your style down to Hemingway or Carver; I’m merely cutting verbiage that strikes me as possibly superfluous. I’m not correct every time, but I’m certainly correct in some instances.”

“The way to straighten a stick is to bend it too far in the other direction.” I love that!

Here is what a sample paragraph of that manuscript looked like with his edits.

The satellite dish was the biggest model the store sold for residential use, twice the size of any his neighbors owned. Delton asked about the really big units—the ones they sold to hotels and apartment houses—but the salesman assured him the model he’d bought would bring in everything that was out there. The man gestured toward the ceiling of the store as he said it and Delton looked up at the white tiles and water stains.

The finished paragraph reads:

The satellite dish was twice the size of any his neighbors owned. Delton asked about the big units they sold to hotels and apartment houses, but the salesman assured him the model he’d bought would bring in everything that was out there.

That’s 42 words. The original was 78 words. Or almost twice as long and didn’t convey a lot more important information to the reader.

I’ve enjoyed the benefits of having some great editors help me improve stories they were about to publish. But editor Nancekeville was rejecting that story. Yes, that was a rejection letter, with actual helpful editing! He did all that to help me learn how to write better. I’ve never seen that happen again in the thirty years since that time. The man was a mensch. He did accept and publish the next story I sent him (without too many edits).

The original “Satellite Dish” story was 23 pages long (double spaced). After three more years of revising and cutting on my own, it was about 13 manuscript pages long when it was published in another magazine called ZYZZYVA. I cut it down even more before it went into my first story collection about nine years later.

I’m not suggesting that you accept every strikethrough an editor foists on you. Only you know what you want your story to look like. That really is up to you. Our micro-memoir class is not intended to make everyone into a flash prose writer. Frankly, I don’t publish much flash fiction or non-fiction myself (Justin does), but I try to apply the principals of careful editing to all my writing. And I love doing exercises that force us to write within narrow word limits. It reminds me again and again how important it is to pick my words carefully.

Obviously, I still fail to do that at times, because writing is always going to be an ongoing learning process. Always. And that’s why we have writing workshops to refresh our craft skills.

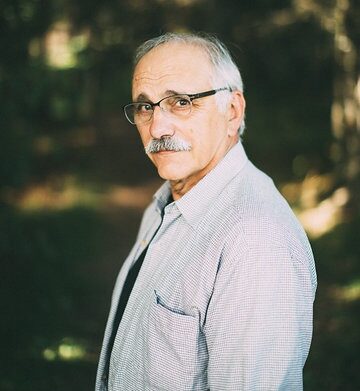

Rich Chiappone, the winner of the 2021 Alaska State Foundation for the Arts and Culture Award, is the author of three story collections and the recent novel The Hunger of Crows. His stories have appeared in the Sun, The Catamaran Literary Review, Missouri Review, ZYZZYVA, and many other magazines. Chiappone taught in the low residency MFA program at University of Alaska Anchorage, is a former senior associate editor at Alaska Quarterly Review, and a long-time organizer of the Kachemak Bay Writers Conference. He lives with his wife and cat in Homer, Alaska. He is teaching the 49 Writers course Friends, Family, and Food: Writing Micro Memoirs About Food in Your Life with Justin Herrmann. You can register HERE.