“Look at the boaters down there.”

As a nonfiction writer with a passion for history and adventure, I sometimes tap webs that link individuals over centuries, millennia even, and thousands of miles apart, individuals otherwise not connected. For the cover of my new collection of Grand Canyon essays No Walk in the Park, I sought an immersive photo from deep within the guts of the great abyss, one that would offer a bottom perspective unlike the abstracted scrimshaw beheld from the rims’ viewpoints. Besides beauty, I wanted readers to glimpse the human past in this place, the risk, hardship, and grit, the continuity between canyoneers then and now.

I had long been a fan of early nineteenth-century black-and-white photos taken before and after the “inverse mountain” became a national park in 1919. Many featured tourists that started to flock to this vertical wonderland by rail, or once Route 66 tied it into the road system, by car. There were stills of a “Tin Lizzy” Model T Ford parked precariously near the edge, and of a hatted, skirted matron who leans and peers over the lip pointing breathlessly at the inner gorge while a second, in a fur coat, grabs the hem of her friend’s cape. Snow mantles the chasm all the way down to the aprons near the Tonto platform, and the gawker does not wear sensible shoes.

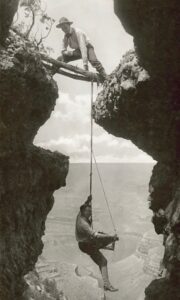

By far the most exciting shots, including many from below the rim, were the lens work of the two Kolb brothers, proto-influencers who ran a studio on the South Rim, making a living by picturing dudes descending on muleback and selling them the prints upon their return. Hailing from Pittsburgh, Ellsworth and Emery had boated the length of the canyon and more on a hardcore trip from Wyoming to the Gulf of California in 1911, bagging the first-ever footage of the gorge’s rapids. The reels they brought home and for decades showed at the studio still are America’s longest-running film. The Kolbs went the extra mile, literally, for that special frisson or angle.

“Hold on just another sec for that money shot.”

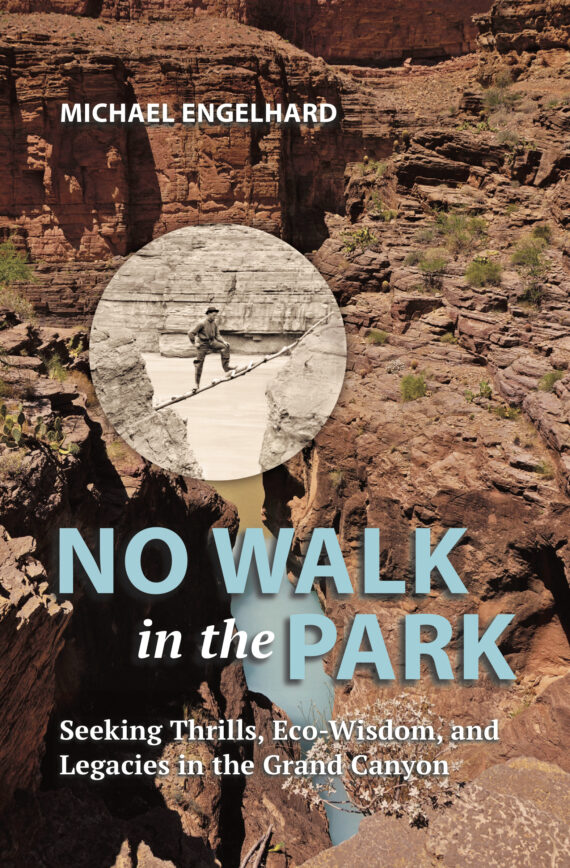

Sifting online archives of the Cline Library’s Special Collections at the University of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, I quickly settled on a clear winner for the cover. In it, the younger Kolb steps defiantly up a rickety driftwood ladder that bridges narrows stories above the river; he seems to be wearing cavalry boots, a blousy shirt, and a black, small-brimmed hat. Beholding them makes your palms sweat.

I realized right away that the photo had been mislabeled as being from Kanab Creek. I knew the place depicted from river trips on which I had worked. I recognized the cove (here sepia-toned) as the turquoise grotto in which we always moored our rafts for day hikes with clients up to the wonders of Havasu Creek. The stream behind Emery’s figure was the Colorado, running muddy, as it always did before Glen Canyon Dam. I could even determine the vantage from which Ellsworth had framed his brother: the trail skipping from limestone ledge to limestone ledge en route to this barebones landing. I had traipsed along it many times at the end of a sun-blasted day spent by the creek’s glowing pools and horse-mane falls.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe are two other photographers whose oeuvre I admire. Their specialty is re-photography, or rather, collages of historical images and their own labor of angles and camera positions researched and meticulously reenacted. Their Grand Canyon work shines in the spellbinding, at times whimsical, Reconstructing the View, a pictorial of double-page panoramas in which the shadows and light of the past blend with those of the present. The splendor, humor, and cleverness of those tableaus sparked the wish for a composition of my own for the cover of my collection No Walk in the Park.

Alas, at the time I lived in Fairbanks, Alaska. A trip south to re-photograph the setting was out of the question, though I felt that I had the exact location nailed down. There was no money for artwork in the publisher’s budget, and the catalogue—showcasing my book’s cover—would go to the printer in less than two weeks.

I trawled the internet listlessly for a suitable image, like a fisherman would an overfished or acidified sea. Within minutes, I did a double take. I clicked on and enlarged a vertical, crisp, well-lit shot of the very same place. Havasu’s waters pulsed neon-blue in the depths, joining a rio muy colorado, both bracketed by the salmon-flesh limestone of the 350-million-year-old Redwall formation. To boot, I could grab a high-resolution, print-quality Flickr file, which came with a Creative Commons license permitting use of the image. As it turned out, a Grand Canyon park ranger on a team-building trip had pushed the shutter button. She described Havasu’s unearthly hue to me as “a color you’d only find inside the glass of a Las Vegas cocktail or as a gummy worm candy.”

When I cropped Emery inside a grayscale circle (suggesting the view field of a spotting scope at an overlook), which I then moved across Erin’s photo on my computer screen, it clicked into a place where it almost perfectly fit. Even Havasu’s cliffs were lining up. It was uncanny, despite the fact that the trail near the mouth of Havasu has few pullouts where an artist might step off-trail and pause, contemplate, and capture this priceless scene.

Strands of visual creativity now bind me to Ellsworth and Emery, to Erin and Byron and Mark, a gossamer circle holding distant strangers.

Alas, the hunt for the perfect picture has a coda. The university press balked at my idea, or perhaps just at too much author involvement. Their counter comps (designer lingo for “comprehensive layouts”) ran the gamut from horsey typography to a concept that reminded the press director of Emerson’s “transparent eyeball” beholding the desert Southwest but in me evoked Hunter S. Thompson’s, glazed with CBD. After repeated exchanges that did not yield any improved designs, I called it quits, kissing the modest advance goodbye, backing out of my contract over “artistic differences.” I then self-published the book, true terra incognita for me, as the canyon at first had been to the Kolbs. I’ve never felt more in charge of my vision.

Trained as a cultural anthropologist, MICHAEL ENGELHARD worked twenty-five years as a wilderness guide and outdoor educator in the canyon country and arctic Alaska. His latest books include Arctic Traverse, a memoir of a solo Brooks Range trip from Canada’s Yukon border to the Bering Strait, and the essay collections What the River Knows and No Walk in the Park. Living in Fairbanks, Alaska, he dreams about relocating to the Southwest—especially on those minus-fifty-degree days.

Dear Michael

You’ve taken the reins this time, and it would be wonderful if you could share some of your hard-won self-publishing discoveries with us.

Anette Coggins

Hi Annette,

Not sure about “taking the reins.” It was more of an emergency solution after I pulled this book from that university press. It has been an interesting learning curve, to be sure. But many other Alaska writers (Nick Jans, Ned Rozell, Kaylene Johnson, and David Marusek, to name just a few) have been self-publishing successfully and much longer than I.