When Jessie Lendennie asked if I had a book to submit to Salmon, I said do you want to see the long version or the short one? She said the long version. That was the “new and selected poems.” Choosing poems was pretty intuitive. I wanted a balance between new and old and I wanted to give each of my earlier books roughly equal space. Essentially, I just went through and picked the poems I felt were the strongest, the ones I tend to include in readings. There were a couple of surprises in the new section, poems that I’d published in magazines but had forgotten about.

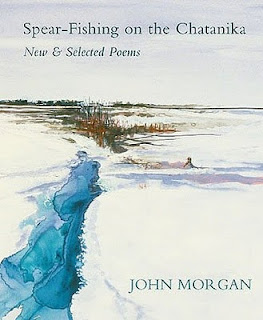

How did you settle on the book title “Spear-Fishing on the Chatanika,” echoing the poem title “Scouts Spear-Fishing on the Chatanika”?

I wanted a title that made a connection to Alaska and that had an element of drama. That poem is a war poem, reflecting back on Viet Nam, and also a father and son poem, and both of those themes run through the book.

There’s so much to savor in this book. Let’s start with poems gathered in groups: “Cape Prince of Wales Alaska: a Suite”; “Six Poems from Above the Tanana”; and “Spells and Auguries.” Tell us about your process of creating poems in groups. Do you set out with that intention, or do you discover the collective energy over time?

Each sequence came about differently. “Cape Prince of Wales: A Suite” came from a notebook I kept during a three day visit to the village of Wales at the tip of the Seward Peninsula. I modeled it on some poems written in numbered free verse sections by John Logan and I knew roughly what it would look like from the start. The poems in “Above the Tanana” are all set at the same location, a ledge overlooking the river with a long view south to the Alaska Range. I wrote one per month for a year, and when I’d written two or three of them I realized what form the sequence would take. Since then I’ve continued to write poems set at that spot which aren’t officially part of the sequence. “Spells and Auguries” took longer to work out. When my son Ben went into the hospital in a coma, I tried to write about it but it was mainly for my own sanity, to keep a grip on who I was. He was in the coma for five days and it changed him quite a bit and changed our lives. I thought I might write a memoir about the experience and went back to the original poems to see what I could draw from them. As I suspected, they weren’t very good, but they brought the experience back to me and instead of a memoir I wrote a sequence of 24 sonnets.

Among your new poems, “Poet Charged in Scrape” is one of my favorites. In it, you turn unfortunate Daniel Poet’s mishap (“The Coast Guard charged Poet with negligence in the accident,” says AP) into a remarkable poem, from “the moon was low and each ripple had tiny sickles darting its peak” to “only a little meaning spilled through the crack in the hull.” When did you know this news snippet had to be a poem, and how did it come together?

As soon as I saw the article in the News-Miner, with a guy actually named “Poet” screwing up and causing the accident, I figured there was a poem in it. I kept the subject in my head for a week or so and when I sat down to write it, it came pretty easily. It’s playful and lyrical in contrast to some of the darker poems in the collection.

In the new poem “Kindling: For Ben,” you’ve written yet another powerful piece generated from the long-term consequences of your son’s childhood illness, a poem that builds on the collection in “Spell and Auguries.” How important is it for poets to probe painful and personal experiences?

“Kindling: for Ben” describes a grand mal seizure and I wrote it because I feel writers need to face their experiences head-on, no matter how painful. Robert Frost called poetry “a momentary stay against confusion.” And the poet Greg Orr tried to spell this out in more detail in an essay he published a few years ago in APR: “Our day-to-day consciousness can be characterized as an endlessly-shifting, back-and-forth awareness of the power and presence of disorder in our lives and our desire or need for a sense of order.” Lyric poetry takes on the disorder and tries to give it a shape. You confront it and then, through the writing, you manage to get some control over it. In this case, though, the control is only at the margin. There’s a breakdown of form in the middle of the poem as the horror of the seizure takes over, and then at the end the form creeps back in in the last couple of stanzas. It’s one of the bleakest poems in the book and I wondered about including it, but I feel the poem that follows, “An Easy Dayhike, Mt. Rainier,” which views Ben’s seizures in a more accepting way, helps to redeem it.

.jpg)