A number of years ago in a fiction writing workshop, a student turned in the early chapters of a novel she’d been working on for some time. The writing was so good that when the class ended I asked her if I could see more of it. After reading it, I ventured an opinion that the first half of the book, which was told through the consciousness of a young girl, was very interesting. But that what then followed—involving a shift in point of view to the girl’s mother—was far less compelling.

I said,” Why don’t you keep it all in the young character’s POV? The events of the second half involve the young girl anyway. She’s still the main character really. So it would not be a hard thing to rewrite.”

The author said, “That’s interesting. That’s exactly what X (a well-known literary agent) said after he too got interested enough in the first pages to request the whole manuscript.”

I knew of the agent she named. He is one of the big guns in NY. Just getting him to ask for the whole manuscript was a dizzying accomplishment. So, I was astonished that the author had resisted his advice. Especially when even she agreed that the novel probably would be better that way. She said she just didn’t want to have to rewrite all those pages.

Well, I can understand why that student might not listen to every single bit of advice I offered, a virtually unknown short story writer from Anchor Point. But to hear the same thing from a highly respected publishing professional? That’s not likely to be a coincidence. And the amazing thing to me was that the author did not doubt the wisdom of the advice, nor did she actually prefer the story told her own way. She simply did not want to do the extra work.

In the end, she self-published a book that deserved a lot more readers than it got, and might have had them too if it had made it to a publishing house. But that would have required more work.

This past spring, I had lunch with a writer friend who had just gotten a six figure advance for a novel. When I asked him about the book’s publication date, he told me that the publisher was making him re-write the last third of it. He was not talking about polishing up the prose. He said they wanted a whole new story line all the way to a whole new ending.

I was astounded. I said, “But they gave you that huge advance. They must have loved the book.”

And he said, “Oh they love the first part of it. They hate the last hundred pages.”

He’s a young guy with three small kids and a less than lucrative job as an adjunct instructor at a state college in the Pacific Northwest. He has no choice but to write a hundred or more whole new pages with completely new plot elements. It’s either that, or give them the advance back.

Last time I heard from him, he was still working on it.

About two years ago, another friend, an experienced author with more than a dozen novels to her name sold what she thought was the already complete manuscript of her next book. Her publisher (with whom she has published several novels) now wants massive changes in the book, whole sections of it deleted and replaced with all new material. Basically, it’s almost as much work as writing a completely new book. What is she doing in response to this crushing setback?

She’s a professional writer. She’s re-writing it.

After twenty years of teaching creative writing, if there is one single thing I’ve seen keeping the most talented students from getting what they say they want (being published), it’s resistance to revision. I don’t know how many times I’ve run into a former student, months or even years after reading their work in a class and I’ll ask about certain story they’d written, a story with so much promise and potential I actually remember it. When I ask if they are still working on it, too many times the answer is that they’ve put it away and started something else instead. Oh dear.

You know, I find those conversations more disheartening than when I meet former students who say they’ve quit writing altogether. That’s unfortunate, but understandable. The long haul of writing is not for everybody. And sometimes it’s good to know when you are not suited for something.

But the new writers who want to do it professionally and just keep throwing first drafts out into the word and wonder why they don’t fly very far are the real tragedies. They have talent, ambition and energy. If only they would learn that successful writing is more hard work than spontaneous creativity. Janet Burroway, the author of Writing Fiction—the best craft book on the subject, in my opinion—says that the word creativity has been so over used that it is basically meaningless now.

And yet, it still has a lot of currency in our culture. Yes, you can get a certain amount of positive attention for being creative (mostly from your friends, family, and public school teachers), but if you want to publish, you really do have to roll up those sleeves and do the hard work of revision.

All of which brings up the question whether this intrusive meddling on the part of creative writing instructors and other “experts” is good for new writers. A fair question. I don’t know. Nobody knows, of course. But I’m inclined to side with Richard Ford who was asked if the harsh critiques handed out in writing workshops might, in fact, cause new writers to give up too soon and quit before they are ready to succeed. Ford’s answer was, “Deciding to write is like deciding to get married. If anybody can talk you out of it, you probably should not be going ahead anyway.”

And (to extend his metaphor) like a marriage, if you are going to commit, be ready to work on it.

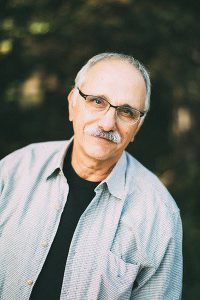

Richard Chiappone is the author of the collections Water of an Undetermined Depth, Opening Days, and Liar’s Code. His stories have appeared in magazines including Alaska Magazine, Playboy, the Sun, and Gray’s Sporting Journal, along with literary magazines including the Crescent Review, The Missouri Review, South Dakota Review, ZYZZYVA, and others. His work has been featured on BBC Radio, and made into a short film featured at international film festivals. An Alaskan since 1982, he is proud to be a member of 49 Writers, and lives in Homer with his wife and cats. He teaches fiction and nonfiction writing for the University of Alaska Anchorage, and for the Kachemak Bay Campus of the Kenai Peninsula College. His latest book, Liar’s Code, is published by Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. of New York City. It is available in both hardbound and electronic editions.