I’m aware of this permeation as I design or write. For me, art and poetry are in things, ideas are in things. They wait. They wait to be realized, interpreted, defined.

In my mind, everything lives in containers. The sea world contains the Sea People, and so on. Mortuary poles contain bentwood chests with cremated remains. Songs contain stories of sorrow, celebration and remembrance. Legends contain lessons for socializing the young. It’s about embodiment.

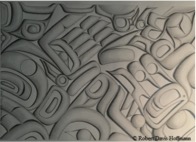

On slow days in the museum, I have my handy sketchbook, because it’s impossible for me not to be inspired when I’m breathing art. I get pretty experimental when I have little to do but sketch. My pages start filling with shapes, concentric, overlapping forms, lines that increase and decrease in tapered widths as is characteristic of formline design. My sketchbook is a curious muddle of Tlingit looking shapes, and starts of poems.

Sometimes creations come “all-at-once” when I visualize an entire design, or when I have an entire poem outline. Here I start with the main structure or framework, and all I have to do is fill in the blanks.

Sometimes creations take shape organically. When I start with a few powerful lines, my free-association propagates more lines. In design, I begin sketching from any point on the canvas and allow the design to develop.

When I create, I give form to a concept, whether by written alphabet, or by the system of formline elements – the ovoid, ‘u’ and ‘s’ shapes, and the negative spaces that result from combining these shapes. My constraints are determined by the surface I’m decorating, and in poetry the lines are limited by page size. They both have visual impact.

Art and writing both have form and content.

In working out form, I consider composition, whether to be literal or symbolic.

In working out content, I consider how to interpret the subject, what it means.

All the rest is about filler, connections, interconnections, allusions, juxtaposition, what to add, what to leave out. As with any creation, knowing when to stop is the difference between good or amateur.

I’m lucky to work in this museum. Quiet time taps me into a source, from which either word or visuals spring. Both essentially allow me to make coherent that which forms in that source. Our Tlingit culture, both the rich past and the current history as it unfolds, are pathways to that place. I live and breathe this. The lighting is dim; the objects seem to glow. How can I not be part of this? How can I not want to interpret this feeling?

Robert Davis Hoffmann is a Tlingit poet originally from the village of Kake, fully engaged in his heritage and culture. He describes the creative impulse for his poetry and carving this way: “My desire to create comes from a drive to connect my past to the present, to redefine the traditional as present day cultural practices.”

You are blessed to work where you do. I remember going into that cold dark building many years ago when it was cared for by sweet elderly Volunteers in Mission.

Intersections: I have a couple of your paintings from years ago when you put some writing in your painting. That is so cool! Keep up the great artwork. Love, ELJ