The typewriter rested on

top of a bookcase at chest height. The writer came to it in the early morning.

Standing, he read the previous day’s work. He had stopped at a place in the

story where he knew what would come next. Then he began again. Between every

two words, he inserted extra space so each word would stand out and he could

better judge its rightness. He was an obsessively methodical writer who took

pains to deliver through his prose a precise mood, certain emotions he wanted

his reader to feel exactly as he had felt them.

top of a bookcase at chest height. The writer came to it in the early morning.

Standing, he read the previous day’s work. He had stopped at a place in the

story where he knew what would come next. Then he began again. Between every

two words, he inserted extra space so each word would stand out and he could

better judge its rightness. He was an obsessively methodical writer who took

pains to deliver through his prose a precise mood, certain emotions he wanted

his reader to feel exactly as he had felt them.

This is the image of

Ernest Hemingway that has stayed with me since my earliest encounters with his writings

and his life of glamour and machismo. Without re-reading everything, I cannot

tell you where I got it. But I can tell you that an October visit to New York City

where I caught “the first ever major museum exhibit” devoted to Hemingway’s work has given me a fresh idea

of just how methodical a writer he was, and it has nothing to do with standing

at a bookcase and inserting gaps between the words.

Ernest Hemingway that has stayed with me since my earliest encounters with his writings

and his life of glamour and machismo. Without re-reading everything, I cannot

tell you where I got it. But I can tell you that an October visit to New York City

where I caught “the first ever major museum exhibit” devoted to Hemingway’s work has given me a fresh idea

of just how methodical a writer he was, and it has nothing to do with standing

at a bookcase and inserting gaps between the words.

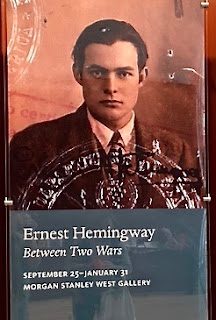

“Ernest Hemingway: Between

Two Wars,” which opened in September at the Morgan Library and Museum and continues

through January 31 before moving on to Boston, ought to be seen by every writer

who has yet to acquire the habit of self-editing and self-revising. Besides letters

from and to Hemingway, notebooks, magazine articles he authored, photographs

spanning four decades, first editions of his books, passports, bullfight

tickets, dog tags, and other papers, including the first Hemingway byline — in

addition to all this, the exhibit notably gives us selected manuscript pages for

a number of Hemingway stories and novels, showing multiple drafts of some works.

These show a tremendous number of cross-outs, insertions, word changes,

re-orderings, and large sections discarded altogether. You cannot avoid the

sense of a writer striving with utmost care to create a certain effect and no

other.

Two Wars,” which opened in September at the Morgan Library and Museum and continues

through January 31 before moving on to Boston, ought to be seen by every writer

who has yet to acquire the habit of self-editing and self-revising. Besides letters

from and to Hemingway, notebooks, magazine articles he authored, photographs

spanning four decades, first editions of his books, passports, bullfight

tickets, dog tags, and other papers, including the first Hemingway byline — in

addition to all this, the exhibit notably gives us selected manuscript pages for

a number of Hemingway stories and novels, showing multiple drafts of some works.

These show a tremendous number of cross-outs, insertions, word changes,

re-orderings, and large sections discarded altogether. You cannot avoid the

sense of a writer striving with utmost care to create a certain effect and no

other.

Unfortunately, the Morgan

does not permit photographs to be taken of the exhibit materials. Its Website,

however, offers several photographs from the show as well as an image of the first

page of the manuscript (literally a manuscript, written in longhand) of A

Farewell to Arms, his second novel. The famous opening of that book is classic

Hemingway, a meticulously drawn, deceptively simple scene-setter that anchors

the reader in a time and place with hints of the action and themes that lie

ahead. But naturally the writer did not come to it right off. The manuscript shows

him heading into a number of blind alleys before correcting himself, editing

and revising as much as he’s generating.

does not permit photographs to be taken of the exhibit materials. Its Website,

however, offers several photographs from the show as well as an image of the first

page of the manuscript (literally a manuscript, written in longhand) of A

Farewell to Arms, his second novel. The famous opening of that book is classic

Hemingway, a meticulously drawn, deceptively simple scene-setter that anchors

the reader in a time and place with hints of the action and themes that lie

ahead. But naturally the writer did not come to it right off. The manuscript shows

him heading into a number of blind alleys before correcting himself, editing

and revising as much as he’s generating.

Hemingway did not like

being critiqued but trusted the criticisms of a select few, who included — for

a time, at least — F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose The Great Gatsby was published

the month before he met Hemingway in Paris in 1925. The following year,

Fitzgerald read a carbon of the second draft of Hemingway’s first novel, The

Sun Also Rises, numbering 130,000 words. As we learn here, Fitzgerald highly praised

it but also suggested a number of cuts, especially the early chapters. As a

result, Hemingway dropped the first 15 pages and trimmed the novel overall to

90,000 words, a 30 percent reduction.

being critiqued but trusted the criticisms of a select few, who included — for

a time, at least — F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose The Great Gatsby was published

the month before he met Hemingway in Paris in 1925. The following year,

Fitzgerald read a carbon of the second draft of Hemingway’s first novel, The

Sun Also Rises, numbering 130,000 words. As we learn here, Fitzgerald highly praised

it but also suggested a number of cuts, especially the early chapters. As a

result, Hemingway dropped the first 15 pages and trimmed the novel overall to

90,000 words, a 30 percent reduction.

The short Hemingway-Fitzgerald

friendship was fraught with tensions, most of it on Hemingway’s side. The

exhibit gives us a choice example of how ungracious he could be. It comes in an

undelivered response to yet another Fitzgerald critique, this one of A

Farewell to Arms. Once again, Fitzgerald expressed great admiration for his

friend’s book but also delivered pointed yet constructive criticisms. (And once

again Hemingway took Fitzgerald’s advice, to the book’s benefit. But he struggled

with the ending, rewriting it almost 50 times until he had gotten it “just

right”; the exhibit contains some of the revised endings.) Fitzgerald’s

comments appear in a long hand-written penciled letter. Below his signature,

written with dark pencil in a neat hand, Hemingway adds tersely, “Kiss my

ass./E.H.”

friendship was fraught with tensions, most of it on Hemingway’s side. The

exhibit gives us a choice example of how ungracious he could be. It comes in an

undelivered response to yet another Fitzgerald critique, this one of A

Farewell to Arms. Once again, Fitzgerald expressed great admiration for his

friend’s book but also delivered pointed yet constructive criticisms. (And once

again Hemingway took Fitzgerald’s advice, to the book’s benefit. But he struggled

with the ending, rewriting it almost 50 times until he had gotten it “just

right”; the exhibit contains some of the revised endings.) Fitzgerald’s

comments appear in a long hand-written penciled letter. Below his signature,

written with dark pencil in a neat hand, Hemingway adds tersely, “Kiss my

ass./E.H.”

That Hemingway wrote in

longhand and in pencil was a big surprise for me. Not just his short stories,

but the early novels in their entirety also appeared at first in pencil. Penciled

manuscripts were a deliberate part of his writing strategy.

longhand and in pencil was a big surprise for me. Not just his short stories,

but the early novels in their entirety also appeared at first in pencil. Penciled

manuscripts were a deliberate part of his writing strategy.

“If you write with a

pencil you get three different sights at [the story] to see if the reader is

getting what you want him to,” he wrote in a 1935 magazine article. The first

“sight” comes when the author reads the completed manuscript. The second

reading is of the typescript based on changes made to the first, and the final read-through

is of the printer’s proofs. “Writing it first in pencil gives you one-third

more chance to improve it. … It also keeps it fluid longer so that you can

better it easier.”

pencil you get three different sights at [the story] to see if the reader is

getting what you want him to,” he wrote in a 1935 magazine article. The first

“sight” comes when the author reads the completed manuscript. The second

reading is of the typescript based on changes made to the first, and the final read-through

is of the printer’s proofs. “Writing it first in pencil gives you one-third

more chance to improve it. … It also keeps it fluid longer so that you can

better it easier.”

Another surprise was how early

his talent flowered. Hemingway’s first published story, “The Judgment of

Manitou,” appeared in The Tabula, his high school’s literary magazine. He was

16. Here is the opening sentence: “Dick Hayward buttoned the

collar of his mackinaw up about his ears, took down his rifle from the deer

horns above the fireplace of the cabin and pulled on his heavy fur mittens.”

his talent flowered. Hemingway’s first published story, “The Judgment of

Manitou,” appeared in The Tabula, his high school’s literary magazine. He was

16. Here is the opening sentence: “Dick Hayward buttoned the

collar of his mackinaw up about his ears, took down his rifle from the deer

horns above the fireplace of the cabin and pulled on his heavy fur mittens.”

The Morgan gives us only

the first page of this story, but we learn there will be a premeditated murder

and a suicide. As one of Hemingway’s biographers wrote, he “had already begun

to work toward the grammar of violence and death that marked his later work.”

the first page of this story, but we learn there will be a premeditated murder

and a suicide. As one of Hemingway’s biographers wrote, he “had already begun

to work toward the grammar of violence and death that marked his later work.”

The exhibit covers

Hemingway’s work and life up until a few years after the Second World War. Following

its showing at the Morgan, it will move to the John F. Kennedy Presidential

Library and Museum in Boston, which owns most of these Hemingway materials.

Hemingway’s work and life up until a few years after the Second World War. Following

its showing at the Morgan, it will move to the John F. Kennedy Presidential

Library and Museum in Boston, which owns most of these Hemingway materials.

Peter Porco, a former reporter for the Anchorage

Daily News, has taught writing at UAA. “The Lady Is a Trucker,” his readers

play, was performed in July as part of Cyrano’s Theatre Company’s theatrical

celebration of the Anchorage Centennial.

Daily News, has taught writing at UAA. “The Lady Is a Trucker,” his readers

play, was performed in July as part of Cyrano’s Theatre Company’s theatrical

celebration of the Anchorage Centennial.

Very interesting! Thanks, Peter.