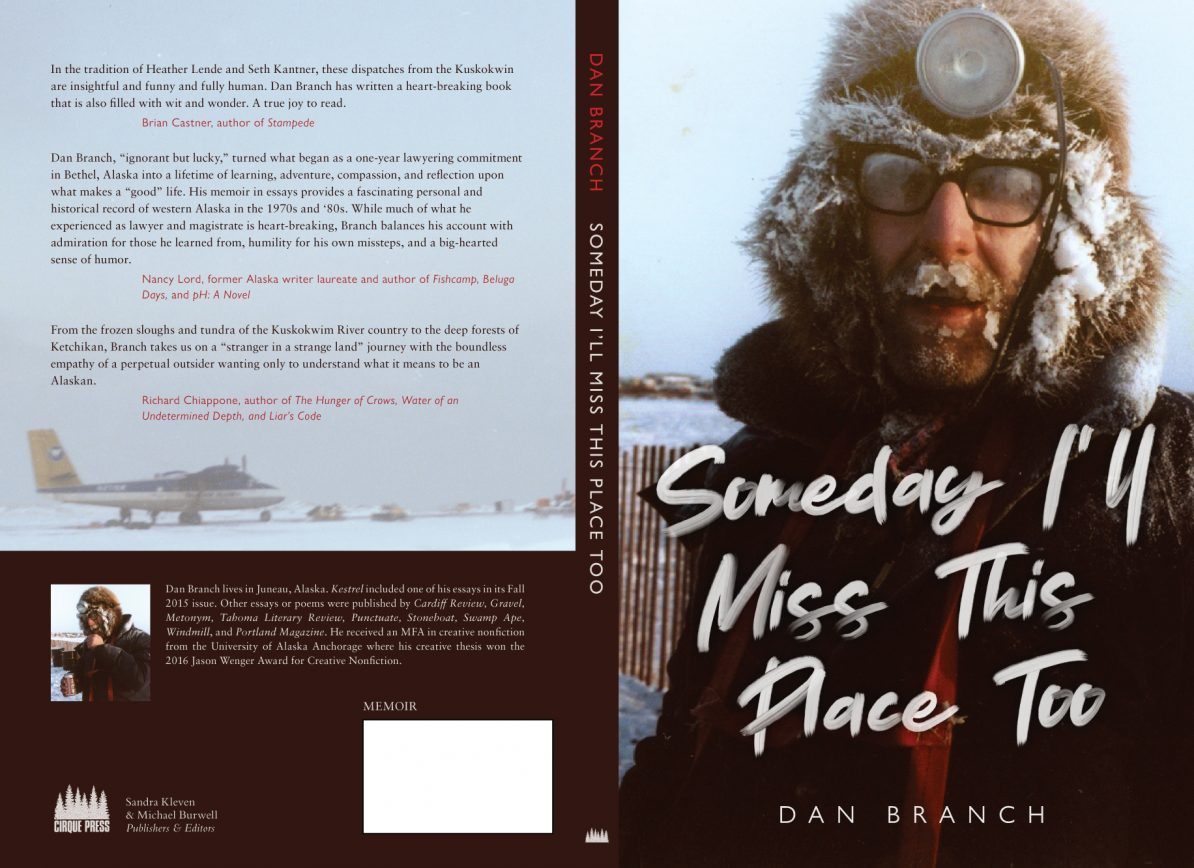

Seven or eight years ago, I retired from a state job and spent years getting an MFA in writing from the University of Alaska, Anchorage. Then I dragged my feet for a few more years before publishing a book of essays. Many describe the lives of friends on the Kuskokwim River of Western Alaska.

You can order, “Someday I’ll Miss This Place Too” on Amazon. Here is one of the essays in the book.

‘57 Chevy

I loaded two Evinrude six-gallon gas tanks into the back of my 1957 Chevy Pickup. Chunks of faded red paint was already flaking off the older tank onto the wood-planked truck bed. The still-bright paint of the other gas can sparkled in the July sun. Next came two wooden oars, a Danforth anchor, bailing bucket, life jackets, food for three days, camp gear, spare clothes, and Bilbo, our lead dog.

Bilbo found a place in the truck bed as far away from the gas cans as possible. As the husky twitched away mosquitoes with his ears, Susan climbed onto the passenger side of the truck’s bench seat. I slid behind the wheel and peered through a filthy windshield for traffic coming down Sixth Avenue. It was five o’clock on a Friday night in Bethel and the way to Brown Slough looked clear.

The truck’s straight-six-cylinder engine banged to life after I pressed the floor starter button with my rubber-soled boot. I was always a little surprised when it started. Keeping the truck alive required friends with knowledge of where the abandoned Chevy trucks were located in the Bethel seawall. When no longer wanted, Bethel cars or trucks were pushed over the riverbank to join the other wrecks slowing down river erosion.

This seawall provided needed spare parts for still operating vehicles. My truck’s original three-on-the tree column shifter was replaced with a four-on-the floor transmission mined from the seawall. When the drive shaft wore out, a previous owner had substituted a slightly longer one from another Chevy. It worked fine as long as you didn’t drive more than twenty miles an hour. The differential would bang into the truck bed once your reached twenty-one.

The worm gear for the truck’s steering was so loose that I had to start spinning the wheel at least fifty feet before each intersection to make a turn. I was already turning it to the left as I let out the clutch and eased into first gear. The truck shuddered and tried to dive off the road and onto the tundra. A spin of the steering wheel to the right kept us on the road. We turned onto Main and rattled our way to the Brown Slough Bridge.

The stern of our sixteen-foot aluminum skiff was floating on the waters of Brown Slough when we arrived. I bought it last summer to replace my leaky wooden river skiff named the Just Barely. Last night, when the high tide had made the slough navigable, I had moved the skiff three winding miles from its usual tie up spot in Alligator Acres Subdivision to the bridge. Sunday afternoon, when we plan to return, water in the slough should be high enough for me to drive the skiff to its home anchorage.

As I loaded gas and gear into the skiff, Susan went to Dundu’s place for a takeaway order of burgers and fries. Dundu’s Korean wife was a great hand with the burgers. I pocketed the Chevy’s ignition key but left the truck unlocked. Bethel had less than ten miles of roads and streets and few places to hide an ancient Chevy pickup truck with “Bethel Migrant Workers” painted on the driver’s side door.

Bilbo refused to leave the truck’s bed, even after Susan placed a bag of Dundu burgers in the boat. I had to carry him into the skiff. There he skulked over to a broad, wooden box with low sides where he would stay until we reached the berry picking grounds. I had to step over him to reach the back of the skiff. Susan pushed us out, climbed over the bow gunwale, and took a seat near the front of the skiff. It never occurred to either us that she should drive.

While we floated down the slough toward the Kuskokwim River, I stood, faced the skiff’s 35-horse Evinrude kicker, and gripped the handle of its starting cord. After two pulls, it purred awake. Sitting down, I slipped ear protectors on and used the motor’s throttle arm to steer us up river. With a Dundu burger in my right hand, I used my left to twist the throttle arm, giving the kicker enough gas to overcome the river’s current. Forward momentum lifted the skiff until it skimmed over the river’s surface.

Squinting against sun reflecting off the river, I steered around a sandbar and into Steamboat Slough. Cottonwood trees lining both banks blocked the wind so the slough waters were flat-ass calm. The skiff slalomed around the curves at top speed. Bilbo hunkered into his wooden box on each turn.

The sound of our kicker echoed off the banks and announced our exit from the slough to a flock of artic terns brooding their young on a nearby sandbar. I muttered an apology as the fierce little birds rose in a cloud above their nests.

Small river swells struck the boat after we passed the tern’s sandbar. A mile upriver, I beached the boat at the base of a tundra-covered bluff. Bilbo leaped out of the boat. Susan pulled it onto the beach. I tied the Danforth anchor to the end of the bow line and kicked its flukes into the sand.

We carried camping gear and food up the thirty-foot-high bluff and on to a spot flat enough for our tent. We staked out the tent, taking care not to crush too many blueberries in the process. After we filled the tent with sleeping bags and self-inflating pads, I carried my meter-long Swedish bow saw to the beach to cut up a green birch tree that had washed up on the beach during the spring breakup flood. Its wood would perfume the house when it burned in our stove next winter.

Designed for efficiency, not safety, the naked teeth of a new Swede saw blade could rip through driftwood almost as fast as a chain saw. Dulled by previously cutting through silt-covered logs, my saw blade bounced off the birch’s bark as I started my first cut. Mosquitoes bit the sensitive flesh along the edge of my baseball cap. Others tried to crawl into my eyes, ears and nostrils. While my attention on the bugs, not the saw, I tried to steady the log by placing my bare left hand a few inches from the blade. Frustrated, skin burning with fresh bug bites, I drove the saw forward. It jumped off the birch log and cut deep into my left thumb knuckle.

I was too stunned to feel pain but shock didn’t blind me to the blood. It formed a red lake in the deep gash then flowed over my thumb and onto the white birch bark. I crushed up a willow leaf and stuffed the cut with it and climbed up the bluff. At the top I fainted, toppling onto the tundra like a windfallen tree.

Accident prone, I always carried a trauma-ready first aid kit. After retrieving it from the tent, I tore the wrapper off several gauze squares with my teeth and pressed them on the wound with my right hand. They slowed the blood flow long enough for me to bite off a strip of adhesive tape and use it to press the gauze over the wound. By this time Susan had arrived with a concerned Bilbo. The husky lowered its ears to half-mast as he watched us pack up the tent and camp gear.

With my left hand raised skyward to keep the wound from reopening, I carried gear to the boat. It didn’t take long for Susan and I to repack it. The adhesive tape securing my makeshift loosened. Blood started seeping from the wound. Worried about infection, and wondering whether we would make it to the Bethel Hospital before it closed for the night, I applied direct pressure on the cut to staunch the fresh bleeding.

The wound prevented me from using my left hand to steer the boat. I could have gripped the throttle with my right hand but I needed it to keep pressure on the still bleeding cut. Susan, who had never before driven the boat, had to get us to Bethel.

We knew many women on the river who could drive a skiff better than me. I had taught two of them what I knew about running their own skiffs. But it never occurred to Susan nor I that she should learn how to bring the Starcraft up on step or make it slice through boat wakes at a forty-five- degree angle. It wasn’t that she couldn’t do it. She just never wanted to learn. That night she had no choice.

Pulling up the hood of her old high school sweatshirt, Susan secured the noise-cancelling muffs over her ears and stood to face the outboard motor. Arms strong from hauling salmon and carrying cans of boat gas, she had no problems pull starting the kicker. Getting the hang of steering took her longer. But soon she was holding a straight course down river.

I was raised by a strong-minded woman who worked as a phlebotomist for the U.S. Public Health Service at a time when it was almost a boys-only club. Her wheat-ranching father died when she was eight. She watched her widowed mother hold on to the ranch in Montana through the Depression years and still manage to feed a chicken dinner every Sunday to her hard-scrabbled cousins. In Mom’s house there were no boy chores or girl chores, just shared chores.

As dusk followed sunset that night on the Kuskokwim River, I was glad Mom wasn’t in the skiff to question how Susan and I had settled into an old fashioned, if not sexist division of labor in our Bethel lives.

My left hand throbbed as we flew past the tern’s sand bar and moved down river to Straight Slough. It provided the fastest route to Bethel. Susan had no problem piloting the skiff around a sand bar and into the slough. Not having to search ahead for snags, I watched a woman cutting fish in front of her family’s fish camp tent. The drawstring of her cotton kuspuk hood was pulled tight to keep out swarming mosquitoes. She would be joining me tonight in the hospital emergency room if while distracted by mosquitoes, she cut herself with the wickedly-sharp uluk she used to slice silver salmon sides away from the fish’s backbone.

After swerving around the sand bar that partially blocked the lower end of Straight Slough, we sped past the shacks of Louse Town. At the mouth of Brown Slough, Susan eased down the throttle and slid onto the beach in front of the ’57 Chevy truck.

We transferred gear and the dog from skiff to truck and secured the boat anchor. Even though she had just done a good job piloting the skiff, she refused to drive the truck because of its dicey steering. After wrapping my wound with more adhesive tape, I started the truck and switched on its weak headlights. We crawled the miles to our house and returned Bilbo to his dog house. He disappeared into it before Susan and I had climbed back into the truck cab.

I muscled the old truck onto Main Street and turned right onto Eddie Hoffman Highway. Named after the town’s traditional chief, it was the only paved road in town. Keeping our speed to under twenty miles-per-hour, I coaxed the Chevy up the highway and into an empty hospital parking lot. The front door of the hospital was locked so we went to the ambulance entrance and looked for the on-call physician’s assistant. Roger, the resident bone setting expert led us to his work station. He showed excitement, rather than sympathy while he removed my makeshift bandaging and injected my thumb with a local anesthetic.

I could see a flash of white bone after he flushed dried blood and chunks of crushed willow leaf from my wound. After that I looked away. Roger used an oversized syringe to wash down the cut with Betadine. While chatting away like a man with too few friends, he stitched a repair of my thumb ligament, sutured up the ragged cut, and used a steel splint and an elastic bandage to immobilize my thumb. Handing me a small bottle of aspirin, Roger warned me that I might lose some function in the thumb.

My immobilized thumb didn’t prevent me from sawing, splitting and stacking firewood that summer. I could still use our 50-fathom drift net to catch enough silver salmon for the winter. I could even drive the ‘57 Chevy truck. But I couldn’t hold on to the dog sled when exercising our team. They needed to train. The following winter we would be running in a 300-hundred-mile dog race. Each day that summer, Susan hitched four dogs at a time to a cobbled-together wooden cart and let them pull her up and down the silt streets of Bethel. By September, my hand had healed enough for me to take over the training.

After work each day, I loaded eight dogs and a sled into the Chevy’s bed and drove through Housing, past the laundromat and the high school to the dump. From there the dogs pulled me and the sled up the Akiachak Bluffs Trail. Years of snow machine and dog team traffic had compressed the tundra under the trail and broken down the little grass islands called tussocks that would have made it impossible to run dogs on the trail without snow cover. The trail provided a challenging but usable path until it ended at the edge of a flooded ravine.

A snow machine or wheeled all-terrain vehicle would have bogged down on the fragile trail. The dogs did not. As they toned their winter muscles trotting on the spongy ground, I helped the sled along by jamming a foot onto the trail, pushing it backwards, and swinging it forward for another push.

As the dogs and I fell into rhythm, I’d swat mosquitoes and try to remember how the trail looked in winter after all the greens had faded to brown, blueberry plants were reduced to leafless sticks, and nothing flew in the sky but airplanes and ravens.

Early the previous winter, before the first snowfall and after an arctic cold snap brought sub-zero temperatures over night, I hitched up a small team of dogs and let them pull me down this trail and then up a newly frozen creek. We traveled over ice so clear that we could see muskrats swimming beneath the sled runners. Only a dog team could travel over such bare ice. Few mushers were willing to risk a slip-and-fall injury to a dog so they waited for snow to cover the trail. But they were training to build up speed for the winter races. Last year, I just wanted to see what was around the next bend and know that it was not going to be another dog team or snow machine.

We never saw another dog team or hunters that summer on the Akiachak Bluffs Trail. But long-tailed jaegers glided over the green tundra, which sometimes moved with mice. Cessna prop planes hauled people, mail, and freight over our heads. Years after I left the Kuskokwim, moose started moving down river to browse on willows along the trail. But the summer I used the trail to train up the dogs, sandhill cranes were the largest animals we saw.

One September afternoon a small “V” of sandhill cranes flew toward us. I heard their rusty-hinge calls before spotting the long-necked birds. Rather than climb out of gun range, as they usually do when flying over men, the cranes eased toward us. They flew in a tight circle low over the team to study us. After three or four loops, they climbed high enough to pass over Bethel without drawing a shot. I told Bilbo to turn around by shouting, “gee haw.”

I felt like God had just granted the prayer I had made each time cranes flew thousands of feet above my head—let them come close enough for me to see if they really have blue eyes like the Yup’ik story tellers claimed. One of my favorite Yup’ik stories was “How the Crane Got its Blue Eyes.” But the eye color of the cranes that circled my dog team that day didn’t matter. I didn’t even think to check. The magic was in the closeness, that the cranes chose to close the distance.

It was wilderness magic, usually only present where the animals are ignorant of man’s violence—remote waters where seals hitch rides on the back deck of kayaks, old growth forests where hummingbirds land on your shoulder and deer cross rivers to investigate a backpacker’s camp.

After I watched the cranes fly over town and then down river, we headed back to the ‘57 Chevy. Without having mastered the steering of that old truck, I could never have driven the dog team under cranes that mistook them for something of their tundra world rather than of man’s.

Great piece. Very Alaskan as I would have expected.

Thank you for sharing that magic moment with the cranes. And for bringing us along on the truck and boat rides, Bethel style. Glad the thumb made it through!