We often pair horror with mortal fear—the sense that one’s life and limb is in danger, but let me tell you a story of true horror.

My parents were artists—painters and etchers—which means I spent an inordinate amount of my childhood at art shows, stealing chocolates from the finger food table and generally being underfoot. I enjoyed it for the most part, and I was genuinely proud of my parents’ work. My father specialized in photorealistic lithographs with political undertones and my mother made brilliant oil paintings that often featured barbies.

So, when she invited me to attend a show while I was home on spring break from college, I happily accepted. Besides, there might be cute boys—seniors from the local branch of UofM who took my mother’s classes. And there were! Several, in fact. One caught my eye, a broad-shouldered young man with a blonde mullet.

You had to be there. It was cool at the time.

Anyway, I got my tiny plate of cheese with a matching tiny napkin and wandered toward him in a way I thought looked very casual. I barely glanced at the painting he was looking at. I was pretty familiar with my mother’s work, but he seemed thoughtful about it, and that was also very attractive.

I said hello. There was banter. There was flirting. He was an artist. He was single. He didn’t immediately ask my cup size. Everything was going absolutely swimmingly, until he gestured to the painting in front of us and said “What do you think of this? Do you think it’s actually the artist’s daughter? I’m not sure how I feel about featuring kids like that.”

For the first time that evening I let my eyes focus on the painting in front of us and felt my heart stop dead in my chest. There I was, painted in loving, obsessive detail—five years old, grinning at my favorite Barbie Doll (rollerblade Barbie) while both the doll and I were completely naked in the bathtub.

Horror.

I think we can all agree horror is the correct emotion to describe this situation, even if no blood was spilled. The genre of horror often means bodies, or maybe parts of bodies, but the heart of the existential fear is vulnerability. Not only are we physically vulnerable, but also known and understood, and therefore outsmarted, in a way that feels dangerous and unacceptable.

The idea of the stranger in our home is terrifying, without even a concrete idea of their intent. To be exposed to danger, to have a safe place invaded, is horrifying in and of itself. It is often remarked that the sex scene in horror is a moral judgement, but I would argue it moreso creates a heightened element of fear by placing characters in their most vulnerable and exposed contexts. How many of us would not be mortified to learn that our intimate moments were being viewed, ax or no ax?

For that matter, intentional embarrassment is not only a part of torturing victims but also creating monsters. Carrie at the prom is deeply embarrassed and her violent reaction seems, if not justified, at least understandable. Jason Voorhees is teased literally to death.

Of course, this embarrassment can get very exploitative, such as the many directors who love to come up with increasingly contrived ways to make their female victims run away from danger dressed only in lingerie. But, if we set these obvious examples of the toxic male gaze aside, we can learn a lot about what characterizes horror aside from fear or anxiety. Horror is closer to love, in that it requires being exposed, known, and vulnerable in a way that humans tend to be very guarded against. The monster or murderer or virus has access to the soft, pink parts of ourselves that we are used to keeping secret.

So, when we start out building the scary inhabitants of our horror stories, it’s tempting to ask ourselves what our characters fear. The answer to that is easy. Murderers. The IRS. Dinosaurs. Sharks. Probably spiders! A better question is—what is the thing about my characters that they do not want to be exposed, that they need to keep safe? In The Shining the hotel doesn’t attack Jack with knives or bullets or teeth. It tears apart his stoic family-man, academic exterior and reveals the shivering, weak addict underneath. Even the average ax murderer doesn’t just ax murder, he reveals the paper-thin veneer of security in the suburbs, in the premise of our safe havens.

Is embarrassment enough to create horror? Obviously not. Afterall, when I saw the painting of myself I simply chocked on a piece of cheese and excused myself, only revisiting the embarrassing memory in the early morning hours when I can’t sleep. But it can be a necessary element to allow the audience not just to empathize with the physical danger, but the existential threat and disorientation of the threat.

There’s no wrong way to get into a story, but I hope this will give you a new way to look at your story and the peril within it. At the very least, let me leave you with a haunting warning about art shows. Beware.

Beware.

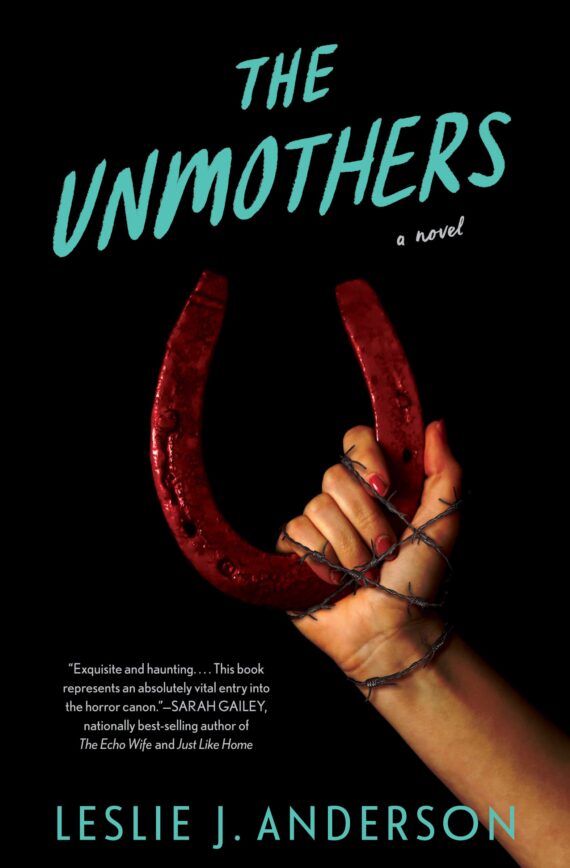

Leslie J. Anderson is teaching the upcoming 49 Writers class, Worldbuilding in Horror. You can register here. She is a writer of science fiction, horror, and fantasy poetry and fiction. Her work has been published in Asimov’s, Strange Horizons, and Apex to name a few. Her horror novel, The Unmothers, is forthcoming from Quirk Books in August 2024. She lives beside a historical cemetery with three good dogs and a Roomba.

Just wish to say your article is as surprising. The clarity to your post is simply

spectacular and that i could assum you’re an expert on this subject.

Well along with your permission let me to grasp your RSS feed to keep up to

date with imminent post. Thans 1,000,000 and please continue the gratifying work. https://Www.Waste-Ndc.pro/community/profile/tressa79906983/